The unseemly and seemly unstoppable rush to zeroism

At the weekend I spoke in Rimini at a gathering of nearly 6,000 students from Catholic universities all over Italy. Aged between late-teens and (a few) mid-twenties, they were members of the Catholic movement Comunione e Liberazione, which was founded in 1954, following an intuition by Fr Luigi Giussani that Italian Catholics did not really understand what Christianity is.

For me as an Irish parent, it was a deeply affecting experience to be among them for the three days of their annual spiritual exercises, to witness their intensity and sincerity, their conversations and questions, their desire to understand what is true and to accompany one another in their searching for it.

I spoke late on Saturday evening — 10pm — at the end of a long day for the students and was once again astonished by the quality of their attention and engagement.

That morning, I had sat in the front row of the auditorium at 9am watching a young man with the voice of an angel warming up his vocal cords, while another young man sat behind him and supported him on an acoustic guitar. Behind me were 6,000 empty seats waiting for the doors to open.

When the two young men finished their rehearsal, the screen over the stage sparked into life and, accompanied by the voice of Maria Callas, began showing images of Antoni Gaudi’s unearthly cathedral, the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona.

Distracted, I lost myself in the emotions the music and pictures were evoking in me. When the screen went dead, perhaps ten, 15 minutes later, I came again to an awareness of my surroundings and, looking around, found that the 6,000 seats had filled up with young people.

In total silence, they had filed into the auditorium and were now behind me waiting for the day to begin.

It would be a mistake to assume these young people to be inordinately pious or submissive. To be truthful, I have never met a collection of young people so intensely engaged with everything — music, life, politics, fashion, art, sport, literature, history, science, economics, social life — or so prepared to question everything.

They talk, laugh, kiss, smoke, drink and dance at least as much and as well as other young people.

At lunchtime on Sunday, as the event was winding down, a group of the students produced a satire of the weekend’s proceedings, including a merciless ribbing of my contribution.

They are as sharp, as fun loving and as open as any kids I’ve ever met, but they live in a parallel universe, in which the greatest questions and possibilities are open on the table all the time.

Reality

The theme for the weekend’s reflections was typical of the great educative genius that was Fr Giussani: ‘The Inexorable Positivity of Reality’, which the students sought to compare and contrast with the bleak, reductionist positivism presented to them as reality by a culture that recognises nothing that cannot be weighed or measured.

The closeness in sound and appearance of the two words, and the total lack of correspondence in their meanings, had been among the main themes of my contribution.

In Ireland, it is impossible to imagine such a gathering. Had I been waiting to speak to a meeting of Catholics in this country, the chances are that everyone in the audience would have been aged 50 or more.

But the age-profile would have been just the beginning of the divergence. Also to be noted is the likely enormity of the disparity of expectation and understanding concerning the terms and limits of a discussion about the meaning and context of Christianity.

And, had this been Ireland, I too would have been operating from a different mental disposition, rummaging around my head for words to bridge the gap between the inevitable expectations of an agenda rooted in piety and moralism and a desire to get, as quickly as possible to what for most Irish Catholics would be an incongruous consideration of the totally human and the totally real.

For these young people, such leaps are axiomatic, inevitable. Indeed, they are not leaps at all, but simply the obvious train of thinking that arises naturally out of the education they are receiving.

To be among such people is to realise how much we have really lost here in this pygmy republic with its smug sense of progress and sophistication arising from its continuing repudiation of a culture 1,500 years old.

To observe and listen to these youngsters is to mourn for our own, cheated of their inheritance of a civilisation that would, if properly presented to them, equip them for the total journey to an infinite destination.

In Ireland today, what is called education is a puny and strangled thing. It prepares the young to rattle around in a reduced and airless culture, in which meanings and possibilities have been plundered of their depth and human resonance.

It sets out to groom the young to insert chips into circuit boards, or regurgitate the formula for a potency drug, but not to know what reality truly is.

It makes ready our children for living in the bunker described so eloquently by Pope Benedict XVI at his speech in the Bundestag in Berlin, a couple of months ago — a bunker constructed of words and thoughts, but with no windows ”in which we ourselves provide lighting and atmospheric conditions, being no longer willing to obtain either from God’s wide world”.

And yet, he went on, ”we cannot hide from ourselves the fact that even in this artificial world, we are still covertly drawing upon God’s raw materials, which we refashion into our own products”.

We, the parents of this allegedly Christian but now almost completely bunkered country, are forced to stand idly by as an avowedly atheist education minister in a stupid Government dismantles the birthright of our children.

Indeed, we are obliged, in deference to the dominant imperatives of ‘tolerance’ and ‘pluralism’ to celebrate this destruction.

Led in conversation by a media lacking the faintest grasp of the consequences of its own vapid anti-religious agendas, we shrug and swallow as we are lectured in the necessity to replace our culture with something presumed to be at once both ‘pluralist’ and ‘secular’, a contradiction-in-terms that should leave any sentient person breathless.

The ‘secular’ dispensation that has suddenly taken over, proposes that religion and education be uncoupled — but without any prior acknowledgment or understanding of the place faith plays in the imparting of knowledge or the understanding of reality.

Rúairi Quinn patronises the Catholicism he appears determined to destroy, emphasising the importance of ”religious education” — as though this was something other than a tautology, as though there existed some other kind of education rather than the total kind.

Of course, the concept of a secular education is an oxymoron.

Propaganda

Education is preparation for life in its profundity, or it is nothing but ideological propaganda. It is strange to note the inversion that has occurred here, whereby the reduction to secularism is seen as the leap of progress, and this, it has to be admitted, arises in part from the reduction of Christianity which preceded it.

But a true education involves a synthesis of tradition and freedom. It takes the child from the imagined moment of human origin to the hypothesised point of destination, enabling him to stretch out his total humanity in the expanse of human desiring and hoping.

It is clear that human beings function to their optimum when given some working model of the whole of reality, which is to say a worldview that is predicated on the infinite, absolute and eternal possibilities of existence. Religion offers a hypothesis that is contingent and yet total, and for this reason enables other forms of knowledge to be placed in a workable perspective.

Minus these understandings, so-called ”religious education” becomes no more than the objectification of religious experience, which in the culture of the bunker reads as ”a history of superstition”.

There is no ‘neutral’ way of imparting knowledge. All teaching carries with it a worldview. The problem is that, with a ‘secular’ education, the worldview comes mainly hidden in the silences, lacunae and elisions of a programme that seeks to produce citizens, consumers and functionaries rather than mature beings animated with affection and curiosity for a life lived in the totality of human possibility.

At the moment, we are allowing those we have seemingly delegated to reconstruct our culture to raise up a new Ireland in which future children will be prepared for work and citizenship, while having their humanity moulded by a disingenuous pluralism, presented and presumed as neutral.

But, really, this neutrality is a slithery dogma that steals from our children the fundamental means to understand themselves. This so-called pluralism is really zeroism — the eradication of the greater part of our children’s humanity, consigning them to the blank space ringed by its defining big fat zero.

Driven by half-wit politicians, aided and abetted by neurotic, spite-filled journalists, and indifferent to the ineffectual protestations of Catholic clerics, this process is unfolding before our eyes.

We have nothing reliable to compare it with, no means of monitoring the outcomes and no understandings by which we might seek to challenge it before it becomes too late. Perhaps it already is.

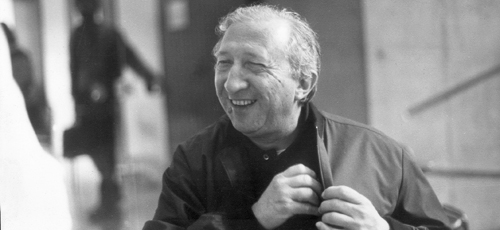

L. Giussani

L. Giussani