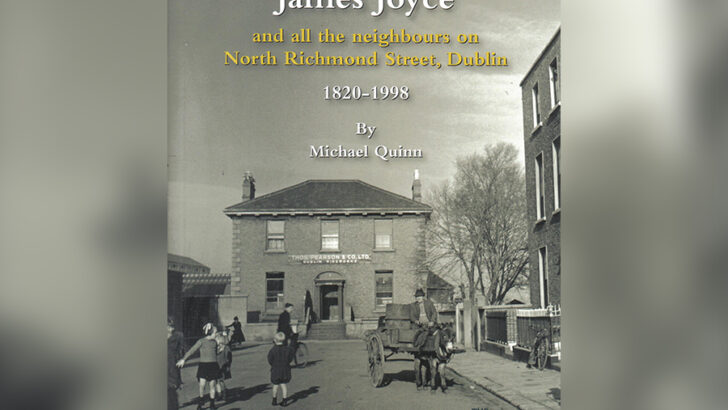

Araby House: James Joyce and all the neighbours on North Richmond Street, Dublin 1820-1998, by Michael Quinn

(The James Joyce Centre, 35 North Great George’s Street, Dublin, €15.00)

The month of June has in recent decades become dedicated to Mr James Joyce. But there are odd overlooked aspects of Joycean Dublin.

Many Joycean writers are anxious to get their hero out of darkest Ireland and into European civilization. Now when interpretation and textual exploration of all kinds are in vogue, mere biographical and social history of Dublin may seem unimportant, which is not the case. There is more to be known.

Sparked

My own interest in Joyce was sparked both my Jesuit education, not at either Clongowes or Belvedere though, and a personal knowledge of some of the places so casually mentioned by Joyce in his essays, stories and books.

This interest has never left me. And preferring to see what can still be explored of Joycean Ireland, I was greatly attracted to this little pamphlet on Joyce and North Richmond Street.

Alas, I find that though the pages are filled with fascinating information about the people who have been involved in the street since it came into existence, Michael Quinn has added nothing to the core mystery, about which indeed he seems a little unfocused.

The problem is simple: when did James Joyce’s family live on the street. He uses it in his story “Araby”, about the bazaar held in the RDS on May 14-19, 1894. Yet other evidence suggests that James and his family lived there on the street in 1895, and that the residence of John Stansilaus Joyce there, perhaps at number 13, was only a matter of months.

Here let me quote myself from my book James Joyce The Years of Growth: (1992). “By an odd coincidence there was another John Joyce living at 17 Richmond Street: he died in 1898, leaving over £20,000 to his widow. His long residence on the street has deceived Joyce’s earlier biographers into thinking that the writer’s family lived on North Richmond Street for several years, but this is not the case: in fact their stay was so brief that it left no record in the usual records. « (James Joyce The Years of Growth, p.134]

By that I meant Thom’s Directory. In Finnegans Wake Joyce suggests the number of their home was in number 12, but that house was occupied from 1870s to 1898 by a doctor›s widow, the Hon. Juliana Michell, a sister of the 3rd Lord Mountmorris, murdered at Clonbur in the Joyce Country during the Land War. She died in 1898 and her son George and his wife moved to Mountjoy Square.

Number 13, however, had been left vacant after the death of Fr. Edward Quaid, whose name is recalled in A Portrait. A brief tenancy between say December of one year and September of the next would pass without note in the directory, as Thom’s lists those who lived in houses when the database closed in November. So the volume dated say 1896, would be of the people there in November 1895, not actually in say May 1896. This simple fact often leaves researchers quite confused.

So we simply do not know exactly what number J. S. Joyce and his brood lived at, or when. But though he casts no light on the Joyce mystery, Michael Quinn has scored a rich haul of facts on the other people who lived on the street and who are entangled as models in the characters in Joyce’s fiction.

Fascinating

For all those who are even slightly interested in Dublin history, this is a fascinating glimpse of life in inner city Dublin. Even those interested only in Dublin will enjoy and benefit from it.

Rarely, if ever, has such a history of the people on one street through a long period of time ever been attempted in Dublin. For this reason alone, leaving the enigmas of the nomadic Joyces out of the matter, it is well worth buying and reading.

But next time Mr Quinn will have to apply himself with a little more diligence. He relies on the decennial census returns, but much more to be learned, say from birth and death records, not to speak of wills and probates. I, at least, sought out the details of the probate of the «Other Mr Joyce», and even troubled myself to visit his grave in Glasnevin, while in search other final resting places there, including indeed that of «The Real Mr Joyce.».

Peter Costello

Peter Costello Araby House: James Joyce and all the neighbours on North Richmond Street, Dublin 1820-1998,

by Michael Quinn

Araby House: James Joyce and all the neighbours on North Richmond Street, Dublin 1820-1998,

by Michael Quinn