Her name was Luca, but her family called her Pearl, and she was one of eight children born into the Henry family in Charlestown, Co. Mayo. Her parents came from a line of teachers whose legacy could be traced to 1844 and the “hedge schools” where the poorest in society got an informal education.

In post-war Ireland, Luca observed her father and mother toil for the good of others, spending hours filling in forms so that illiterate neighbours could claim state benefits.

She also came to know the power of education as a force for social change. “Not as sudden as a massacre,” remarked author Mark Twain. “… but more deadly in the long run!”

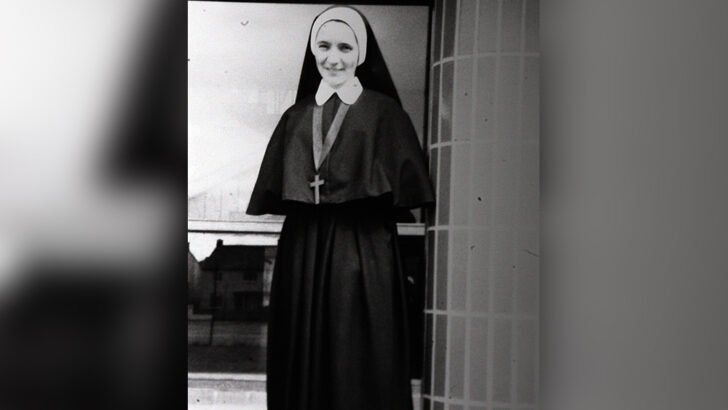

Luca was top of her class at Trinity, and even won a place at the Sorbonne in Paris. But instead of marrying, this pearl of great price became Sr Luca, after entering the St Louis Order in Monaghan as a young girl in the 1950s. “What a waste!” a male contemporary later remarked, because, under that veil, Luca Henry was a dark-haired beauty. “She had the world at her feet but she gave it all up.”

I thought of Luca – who passed away just over a year ago – and many like her, while reading the latest statement from the Association of Catholic Priests Ireland which has condemned the scapegoating of religious women.

Unjust

The association said these women took up the work that the state was either unwilling or unable to do, and are too often depicted in the media as “harshed faced nuns” in habits. “It is false, and unjust,” said the association.

The association is a rather rebellious liberal lot, but on this occasion, I found myself applauding.

Many of these elderly nuns, said these priests, were now “too frail or frightened” to try to set the record straight, fearing they would be “showered with abuse” from many, many quarters.

“We know them and the hurt they experience by this portrayal. The reality is that most have lived quiet, hard-working lives with a minimum of financial reward.”

The ACP went on: “Many people were lifted out of poverty and lived successful lives because of the education provided by the religious women.”

Indeed tens of thousands of young women in West Belfast were empowered by the schools run by religious sisters such as Sr Luca.

Sr Luca was kind, and understanding, but she was also tough. ‘With Luca,’ said one admirer, “the children always came first’”

When the St Louis Order founded St Genevieve’s Secondary School in working class West Belfast in 1966, Sr Luca and the other religious put their wages back into the school. They had come at the invitation of the Diocese of Down and Connor, which was desperate to have a girl’s secondary school in this deprived area. Soon the Troubles had broken out, but Sr Luca persevered, like many southern Irish women religious, who had effectively moved into a war zone. “They called us the white martyrs,” chuckled one such sister with a country lilt who had come to visit my convent on the Falls Road. “Steel magnolias!” I thought to myself.

Sr Luca was kind, and understanding, but she was also tough. “With Luca,” said one admirer, “the children always came first”.

As principal in the 1980s, she spearheaded a campaign for a new building for St Genevieve’s which along with other religious run schools in West Belfast – such as St Dominic’s, St Rose’s and St Louise’s – has lifted generations of young women towards further education and professional life. Indeed one of St Genevieve’s graduates, Cathy Austin, a lay woman, is now acting principal.

Of course there are no statues, street plaques or gable walls dedicated to Luca or any other women religious in the city. “Eaten bread, soon forgotten”, a fellow reporter used to mutter when faced with ingratitude.

The Association of Catholic priests has accused some media of judging the past harshly, ignoring the context, while trying to outdo each other in “condemnation”. “Hindsight alters perspective,” it said.

Many religious, it also claimed, now regret that their orders ever took on industrial schools, orphanages and mother and baby homes, providing services to single pregnant women “who no one wanted to help” – including their own families.

Culture

When I was a child at Catholic school in Toronto, in the early 1970s, the old culture, where children were “seen and not heard”, was disappearing fast. But I do remember the ruler being used and, and how a little girl in my class who had her curly red hair pulled, quite viciously, by a teacher, who was a lay woman.

No one, including the ACP, is asking for cover-ups, just, in the words of these priests: fairness, balance and perspective.

Columnist Mary Kenny recently noted how Hollywood has dramatically shifted in its portrayal of nuns, from angelic to demonic. Indeed I recall, about seven years ago, several odd incidents in Belfast, when my sister and I were strolling along in our brown habits: a group of little girls coming our way suddenly screamed and ran away in mock terror. It was later explained to me that there was a new horror film out about nuns.

Many times in my life, I have encountered nuns with a vinegar face, and this is not friendly’”

Even Pope Francis, however well-meaning, can be insulting and patronising to women religious. In off-the-cuff remarks reported just days ago, the Pontiff told a group of missionary sisters to steer clear of gossip, and not to look sour. “Many times in my life, I have encountered nuns with a vinegar face, and this is not friendly,” he said. “This is not something that helps attract people.”

Holiness

Holiness is indeed attractive, and the weekend media coverage of Sr Clare Crockett being made a Servant of God was a light in the darkness. This Derry girl, killed, aged 33, in an earthquake in Ecuador, deserves the title, Servant of God. She was undoubtedly an exceptional young woman, who gave all for God, but she is not alone when it comes to exceptional religious women.

I lived for five years with some heroic sisters who quietly served for decades, among them Sr Magdalene Bishop, a convert from London and Sr Marie-Dolores O’Brien, from Ferns Wexford, who died not long after Sr Luca.

They are the last in that generation of religious women who fell in love with Jesus, took the Gospel to heart, and poured themselves out with great faith, hope and love, over many decades. They were not hard-faced nuns in habit, but steel magnolias, tough and kind women, white martyrs who ‘spent themselves for Christ’ and left more than footprints of faith.

Martina Purdy

Martina Purdy Sr Luca Henry.

Sr Luca Henry.