The ghosts of Lafcadio Hearn

The Little Museum of Dublin has been running an exhibition devoted to Lafcadio Hearn, “the writer on Japan”, as the reference books once used to say. The revival of interest in Hearn in Ireland has been due to the enthusiasm of former ambassador Paul Murray, who through his biography of the writer and countless talks, has promoted him actively.

But though he had an Irish father Hearn’s mother was a Greek, so just how much of an “Irish writer” Hearn (1850-1904) was remains problematic.

He was born in Lefkada, after which he was named, one of the Ionian islands, then a British protectorate. His parents dying early, he was brought up in Dublin by a series of aunts – and a plaque in his honour is on a childhood home in Upper Leeson Street. It cannot, of course, be read because of electric gates. There is something symbolic about that. One can know about Hearn, but not approach too closely to him. There is something elusive about him.

After finishing his education he was sent off to the US to make his own way in life. From there he went on to Japan in 1890. Marrying there he began to interpret that oriental civilisation to the West in a series of books which critics and readers found “charming and delicate” – which is not always the tone of Japanese literature.

However, it has to be said that his reputation faded after his death. When translations from the great span of Japanese literature began to appear in the 1920s and 1930s, such as Arthur Waley’s monumental version of The Tale of Genji, which was to be followed by many other works by other translators who brought the work of everyone from Sōseki to Mishima before western readers, Hearn’s version of Japan came to be seen as an aspect of the vogue for Japonaiserie that that swept the west in the last half of the 19th Century – of which a Japanese prints, porcelain and Madame Butterfly were all a part.

Nothing in Hearn explains those aspects of Japanese character that gave rise to the Nanking Massacre, Pearl Harbour, or the abuse of the “comfort ladies”.

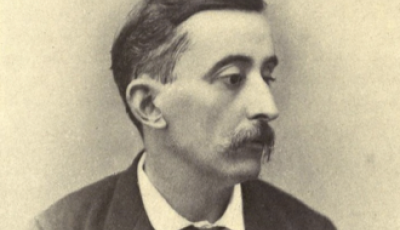

Yet Hearn was undoubtedly a writer of some status. I own a set of Harper’s Monthly, a great American magazine of the period. In the issue for March 1887 there is a portrait of Lafcadio Hearn in an article about “the new movement in Southern literature”. Many of the names mentioned are now little read, except Joel Chandler Harris and Hearn.

In America, Hearn had worked first for Northern newspapers. Having made his name as reporter and storyteller, he moved south to New Orleans, where the exotic atmosphere of the French Creole and Black city caught his imagination. I would think that as “a Southern writer”, Hearn is of more importance than as interpreter of Japan – though Paul Murray would not agree with this.

He published many articles (often in Harper’s) and as well as three books about Creole culture – including a Creole cookbook. Harper’s sent him to the French island of Martinique for two years, which produced another important book.

More than that: a friend of Waley’s, the poet Sacheverall Sitwell (the little brother of Edith and Osbert) remarked that Hearn, “who wrote in an irritating and affected style when he reached Japan, is at his best in describing Martinique and Guadeloupe”.

Hearn is these days credited with inventing the “idea” of New Orleans as a special place, a melting pot of races and culture. His ethnographic writings have been collected and published by a university press, and his American writings now also find a part in the prestigious American Library series.

While in the US he also wrote Stray Leaves from Stray Literatures and Some Chinese Ghosts. In Japan, he continued this theme of the strange, the bizarre and the ghostly in his work.

I have wondered if this taste for the occult and the mysterious does not betray his real Irish heritage. After all, he came from the country of Poe’s ancestors, of the Brontës, and of Bram Stoker. Here perhaps we catch a flavour of what might now be called “the Celtic temperament”, applied to then little regarded cultures.