Welcome to the world of alternative truth

The row that erupted after President Trump’s inauguration between Team Trump and the media about the attendance at the inauguration has thrown up some interesting attitudes to what some of us I suppose are old fashioned enough to call ‘truth’. Pilate may have turned away with the philosophical comment “what is truth?” and washed his hands of the crucial matter brought before him; but few others can really do that.

The media were right in suggesting that the crowds were in fact thinner than for president Osama’s inauguration. The Financial Times carried a ground-level with a caption pointing out the large gaps between people. But Team Trump wished to include in the figures those who watched on TV round the world. But they are hardly attending in the sense of being present. Having promised the greatest inauguration of all time, Trump cannot bear to be seen to have failed. To his TV-fixated mind, ratings matter.

In the course of the altercation a Trump spokesperson said it was their aim to present “alternative facts”. The New York Times remarked that this was a synonym for lies.

A mere by-liner like me hesitates to disagree with the august oracle of 620 Eighth Avenue. But surely there are alternative facts. Certainly they are well known to historians.

If one were writing a narrative history – a thing few historians actually do these days – one would construct the narrative on the basis of a selection of facts between which one established a linkage or continuity, leading to a conclusion about an historical event, let us say, Easter 1916.

However, another historian approaching this problem might well select an alternative set of facts and arrive at a very different conclusions. Some people call this ‘revisionism’.

A Hegelian (a polite term these days for old-fashioned Marxists) would say this thesis and antithesis would in the end produce a synthesis. And that is indeed more or less how the writing of history proceeds, through a system of argument and counter-argument, in other words debate and dialogue.

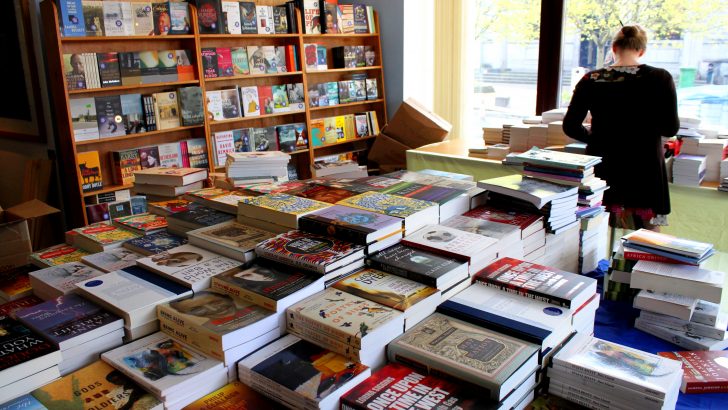

But alas ‘alternative facts’ has these days quite another meaning. In any large bookshop – the kind of thing that is becoming rarer these days – one will find perhaps close to that section dealing with ‘Mind, Body and Spirit’ a smaller section entitled ‘Alternative History’.

Here might be found such creative works as The Holy Blood and The Holy Grail, which gave rise to Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. Mr Brown was, however, writing a novel; the work of Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln claimed to be fact. Certainly it read with a brisk determination not to let the reader pause to think. But the book certainly had “facts” (factoids perhaps) in it, but also a lot of untruths (or rather lies).

Cover-up operations

An even more surpassing best seller was The Tomb of God in 1996. This can now be bought on line for £0.01. It is described by Amazon as “an exposé of one of the greatest cover-up operations of all time”. In 1992, two men undertook to solve an ancient mystery; their discovery involves the search for “one of history’s greatest treasures and includes paintings, coded messages, maps, murder and gold”. The gist of it was that the body of Jesus is hidden away in at tomb in the south of France on Mount Cardou, near Rennes-le-Chateau, of course.

Need I go on? The mystery of Rennes-le-Chateau at the heart of the these two books is in fact no mystery. The mysterious local parish priest was a clerical racketeer who made a fortune accepting money for Masses he never said, but, as Christopher Howse has observed, the books containing the facts about his life being in French, are unread in the English-speaking world, in the UK and US. There it seems readers prefer ‘alternative facts’.

Books such as The Holy Blood and The Holy Grail and The Tomb of God and countless others whose titles may be less familiar to most readers, have inured people to accept that the academics and others who reject these notions, those much derided “experts” of recent election controversies, are intent on hiding “the truth” from the public.

All too often we attribute our own worst intentions to our opponents, for it is politicians who all too often lie and cover up, not historians. Historians are among nature’s blurters.