All the current talk about judges and courts made me reflect this week on the role of law in Christian civilisation. The institutions of justice are not, of course, a Christian invention; it was the pagan Romans who were the pioneers in legal thought and practice. It was they, for example, who first enunciated the principle that all citizens were equally subject to law.

When Romans became Christian, they happily baptised their legal tradition too, and the first Christian emperors were eager inheritors of Roman law. Justinian, who ruled in the 6th Century, played a particularly important role in commissioning the gathering and harmonising of centuries of laws and judgments into a single code. The task seemed impossible, Justinian remarks in the Code’s prologue, but he confided the whole task to God, the source of all justice and power.

Heritage

While Justinian admired greatly the heritage of Roman law, he recognised too that there are laws that are unwritten, and no less binding for all that: “Those rules prescribed by natural reason for all men are observed by all people alike, and are called the law of nations.”

What Justinian calls “the law of nations” other writers call “natural law”: principles for human flourishing which can, in theory, be arrived at by reflecting rationally and carefully on human nature.

This notion is central to all Christian thinking on law. Written laws change, and vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but the natural law endures. Even if wicked earthly powers succeed in changing written laws to suit their ends (as Adolf Hitler did, for example), their actions are nevertheless judged by the unchanging standard of natural law, which they have no power to change. An action might be legal while being terribly unjust.

Long before the conflict with Henry VIII, More had argued that the ‘mutual consent of men’ is never enough to make a law just…”

In Faculties of Law today, however, it is distinctly unfashionable to think in terms of natural law, or to point to any grounds for law beyond the written laws themselves, beyond the will of legislators. This philosophy of law makes it near impossible to speak coherently about laws being either just or unjust. According to this way of thinking, justice is simply the same as legality.

The older tradition is, on this point, more radical. Think of St Thomas More and his bold refusal to submit to the crown. In his Utopia, written long before the conflict with Henry VIII, More had argued that the “mutual consent of men” is never enough to make a law just, and that human laws should be rooted in divine justice.

This understanding of the limits of merely human justice is what led More eventually to declare on the gallows with such clear conviction that he was “the king’s good servant but God’s first”.

The very same principle gave force to Martin Luther King’s arguments against racial segregation. His famous ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ appealed to St Thomas Aquinas’ understanding of natural law, and defined an unjust law as one “out of harmony with the moral law”. The whole civil rights movement was founded on the idea that there is a justice beyond written laws, a justice which places real and urgent demands on us all.

This week is the traditional time of year ‘Red Mass’ celebrations, where judges and lawyers take time to worship the Lord “who loves justice” (Is 61:8). Such gatherings might not be happening this year, but the need has never been more urgent for legal professionals, and for all of us, to recognise and honour the timeless source of justice beyond our human judgments and laws.

Sting in the tale

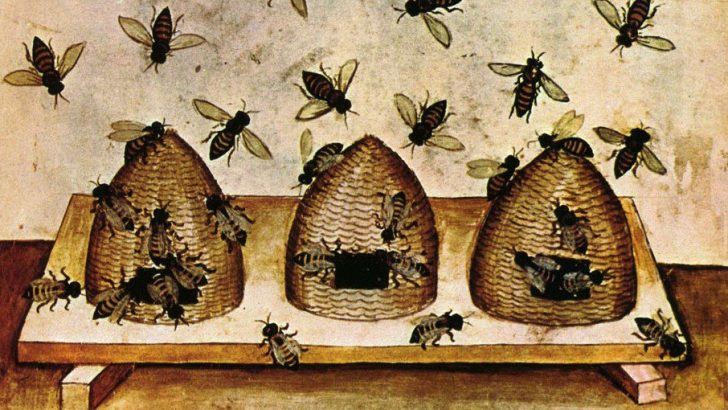

One of my favourite texts of early Irish law is ‘Bechbretha’, an 8th-Century tract on beekeeping. It’s a simple set of rules about the rights of landowners and beekeepers themselves.

Bees naturally wander beyond the land of their owner, and the law here states that farmers on adjoining lands, whose flowers feed the bees, are entitled to a little honey each year as payment for the nectar.

If a swarm departs the beekeepers’ land and settles in a tree on the land of another, the two farmers’ divide the honey in half for three years, after which the new beekeeper gains full rights over the bees.

While the word ‘justice’ makes us think of weighty and controversial issues, these wise old rulings remind us that no matters are too small for fairness to apply.