Listening will only get the Church so far if it doesn’t trust its own Tradition, writes Ruadhán Jones

Let’s cut to the chase; why does the Church want to reach out to those outside it, many of whom are hostile to it, some of whom have already rejected it? Wouldn’t it be easier if the Church settled for becoming smaller, more homogenous and simpler to manage?

The answer to the second question is probably yes, but the Church doesn’t think this way and for a particular reason – we believe we have the keys to eternal life. Our mission is to share the good news that others can join the eternal wedding banquet with Christ, the bridegroom, in Heaven.

What brings this thought to mind are two things. First, the announcement of our own national synod in five years’ time. And secondly, an interesting report by a US agency – the Springtide Research Institute – on the relationship between young people and religion entitled, ‘The State of Religion and Young People’.

The mission of the synod is to reinvigorate the Church in Ireland and to set it on a path for the future. It proposes to do so by “outreach to the peripheries”, listening to what people, young and old, within and without the Church, have to say about the Irish Church’s past, present – and future. What are we likely to hear? And what should our response be? A tentative answer to these questions, at least in relation to people aged between 13-25, is hinted at in the aforementioned report.

Loneliness

The report suggest that loneliness is one of the major issues facing young people. In particular, a lack of trusted adult mentors affects them badly: 40% of participants report they have no one to talk to and half report that their life has no meaning. Young people who have one trusted adult in their life are more likely to express satisfaction than those who don’t, by a difference of 20%, and it increases the more trusted adults they know. Then why don’t they have more interactions with trusted adults?

The report proposes a few answers to this question. One is that “the fabric of society” has broken down. As communal structures are dismantled by a culture which demands mobility as one of its primary virtues, a young person’s community is reduced more and more to family or friends.

Around 75% of young people turn to their parents when looking for support, according to the report. Religious leaders come in at 8%, behind coaches (9%) and teachers (17%), who are the most trusted authority figure in the lives of young people aside from the family. Young people are leading an increasingly isolated life.

This is also a result of a gradual erosion of trust in institutions among people of all ages. It is not just religious institutions, as David Quinn pointed out April 8; this is across the board. It is an effect of post-modernism and one the Church needs to be aware of; in attempting to liberate us from traditional forms of community, it has taken us back to one very ancient form – tribalism. Postmodernism and tribalism themselves are a consequence of the collapse of post-war rationalist optimism, which left a vacuum that nothing has filled except the irrational ideologies of modern elites and the tribal sub-groups over which they rule. Either through blood ties or through shared views, people group into tight-knit communities, impenetrable from outside. They neither desire nor seek an ultimate authority.

Desire

What young people do desire are relationships. That is because for them, says the report, identity “is increasingly seen as something that each individual personally constructs piece by piece, rather than something handed down from a prior generation or imposed by a community”. To assess character implies a communal, cultural understanding of what it means to act as a particular person in a particular role. Young people – and adults – lack that context and are unable to judge goodness or badness, or to suggest any way forward apart from personal choice.

That doesn’t mean they are amoral. But it does mean their morality and convictions are tied to ‘personal belief’ or ‘convictions’ and not an ‘ethic’ or ‘religion’. Challenges to a person’s choices are, as a result, interpreted as being a personal attack, rather than an assessment of their character, and reinforce tribal associations. What they desire are relationships of company and support as they explore and define their own identities. Empathy – experiencing as I experience – and listening become the key virtues.

It is fortunate, then, that empathy and care are two of the Church’s charisms. The Church, by virtue of its temporal organisation, is present everywhere, in small villages and big cities, isolated rural communities and cosmopolitan urban hubs. As a result, it is always present in, as the report puts it, “the messiness of the present moment” and provides a community outside the family or clan. It is “the People of God” which, “whilst remaining one … is to be spread throughout the whole world” (Lumen Gentium, 13).

But presence and empathy are not enough, even though these virtues are constantly referenced in modern life as the balm for every ill. Empathy enables us to understand a person’s problems, but it can also lock us into their vision of these problems. When preparing for the Synod, we must bear this in mind. It is highly likely that people writing in with proposed solutions will in fact be presenting what is a symptom of our society’s malaise. Listening, care and empathy are all elements of the Church and a point of connection for us. The emphasis placed on them by post-modern cultures hints at the hurt people are feeling and their inability to deal with it. Young people want to be treated with care because they are hurt.

Faith

But the Faith is more than a therapeutic response to the troubles of the world; it calls people further, to acknowledge the reality of suffering and sin, and to take up our cross knowing that God’s love makes our burden light. The Church didn’t create suffering or sin, but it has to begin by acknowledging them – without that starting point, all we do is manage the symptoms, not strike the root.

Though they may not ask for it in their synodal submission, what young people need is the challenge of the Church’s authority as well as the balm of its community. This is an authority handed down to us by God of which we are stewards and teachers, and which we have a duty to pass on.

The Church has a responsibility to elevate people so they can see beyond the limitations of a fragmented society. The Church has to trust that it has a set of truths to teach people, independent of this or any society, which are the prelude to actually experiencing the truth itself, the source of our being. We have to trust we are the ultimate authority which most have given up on finding – and yet still need.

Ruadhán Jones

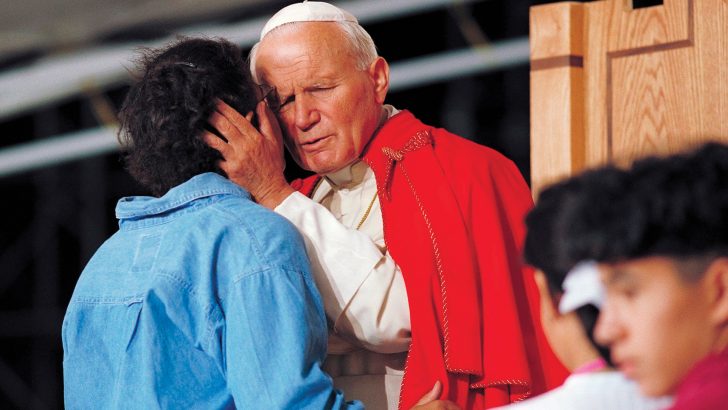

Ruadhán Jones Pope John Paul II

embraces a young woman during the closing Mass of World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. Photos: CNS.

Pope John Paul II

embraces a young woman during the closing Mass of World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. Photos: CNS.