We no longer understand melancholy. Today we lump all forms of melancholy together into one indiscriminate bundle and call it ‘depression’. While a lot of good is being done by psychiatrists, psychologists and the medical profession in terms of treating depression, something important is being lost at the same time.

Melancholy is much more than what we call ‘depression’. For better and for worse, the ancients saw melancholy as a gift from God.

Prior to modern psychology and psychiatry, melancholy was seen precisely as a gift from the divine. In Greek mythology it even had its own god, Saturn, and it was seen as a rich but mixed gift. On the one hand, it could bring soul-crushing emotions such as unbearable loneliness, paralysing obsessions, inconsolable grief, cosmic sadness and suicidal despair; on the other hand, it could also bring depth, genius, creativity, poetic inspiration, compassion, mystical insight and wisdom.

Human finitude

No more. Today melancholy has even lost its name and has become, in the words of Lyn Cowan a Jungian analyst, “clinicalised, pathologised, and medicalised” so that what poets, philosophers, blues-singers, artists and mystics have forever drawn on for depth is now seen as a ‘treatable illness’ rather than as a painful part of the soul that doesn’t want treatment but wants instead to be listened to because it intuits the unbearable heaviness of things, namely, the torment of human finitude, inadequacy and mortality.

For Cowan, modern psychology’s preoccupation with symptoms of depression and its reliance on drugs in treating depression show an “appalling superficiality in the face of real human suffering”.

For her, apart from whatever else this might mean, refusing to recognise the depth and meaning of melancholy is demeaning to the sufferer and perpetrates a violence against a soul that is already in torment.

And that is the issue when dealing with suicide. Suicide is normally the result of a soul in torment and in most cases that torment is not the result of a moral failure but of a melancholy which overwhelms a person at a time when he or she is too tender, too weak, too wounded, too stressed or too biochemically-impaired to withstand its pressure.

Leo Tolstoy, the Russian novelist, who eventually did die by suicide, had written earlier about the melancholic forces that sometimes threatened to overwhelm him. Here’s one of his diary entries: “The force which drew me away from life was fuller, more powerful and more general than any mere desire. It was a force like my old aspiration to live, only it impelled me in the opposite direction. It was an aspiration of my whole being to get out of life.”

There’s still a lot we don’t understand about suicide and that misunderstanding isn’t just psychological, it’s also moral. In short, we generally blame the victim: if your soul is sick, it’s your fault. For the most part that is how people who die by suicide are judged.

Even though publicly we have come a long ways in recent times in understanding suicide and now claim to be more open and less-judgmental morally, the stigma remains. We still have not made the same peace with breakdowns in mental health as we have made with breakdowns in physical health.

The person suffering from leprosy still had the consolation of not being judged psychologically or morally. They were not judged to be ‘unclean’ in those areas. They were pitied”

We don’t have the same psychological and moral anxieties when someone dies of cancer, stroke or heart attack as we do when someone dies by suicide. Those who die by suicide are, in effect, our new ‘lepers’.

In former times when there was no solution for leprosy other than isolating the person from everyone else, the victim suffered doubly, once from the disease and then (perhaps even more painfully) from the social isolation and debilitating stigma.

He or she was declared ‘unclean’ and had to own that stigma. But the person suffering from leprosy still had the consolation of not being judged psychologically or morally. They were not judged to be ‘unclean’ in those areas. They were pitied.

However, we only feel pity for those whom we haven’t ostracised, psychologically and morally. That’s why we judge rather than pity someone who dies by suicide. For us, death by suicide still renders persons ‘unclean’ in that it puts them outside of what we deem as morally and psychologically acceptable.

Their deaths are not spoken of in the same way as other deaths. They are doubly judged, psychologically (‘if your soul is sick, it’s your own fault’) and morally (‘your death is a betrayal’). To die by suicide is worse than dying of leprosy.

I’m not sure how we can move past this. As Pascal says, the heart has its reasons. So too does the powerful taboo inside us that militates against suicide.

There are good reasons why we spontaneously feel the way we do about suicide. But, perhaps a deeper understanding of the complexity of forces that lie inside of what we naively label ‘depression’ might help us understand that, in most cases, suicide may not be judged as a moral or psychological failure, but as a melancholy that has overpowered a suffering soul.

Fr Ronald Rolheiser

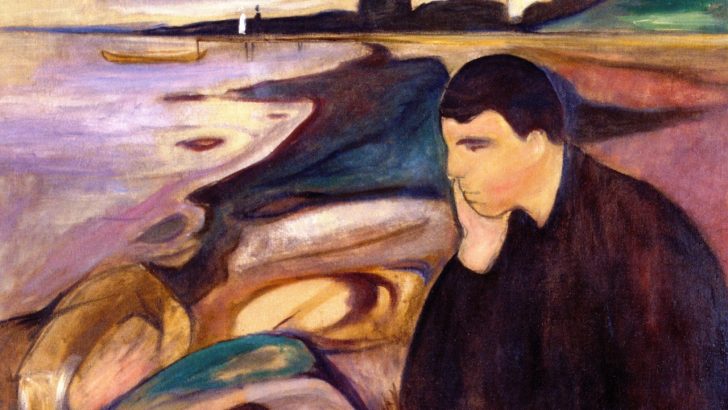

Fr Ronald Rolheiser ‘Melancholy’ by

Edvard Munch

(National Gallery,

Oslo).

‘Melancholy’ by

Edvard Munch

(National Gallery,

Oslo).