Gutenberg’s Cradle : Incunables at Marsh’s Library, Dublin,

a catalogue compiled by Sara D’Amico

(Marsh’s Library with the support of the Consortium European Research Libraries and the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, €20.00; can be ordered directly from information@marshlibrary.ie)

We are continually told that living as we do in an era of immediate electronic communication, the era of the book as we have known for approaching 600 years, is dead. In the very near future books, like newspapers, will simply disappear. So they say.

But as someone raised in a house filled with the books of several generations, into which five newspapers a day came for business reasons, all of which I looked into growing up, I am one of those who are firmly convinced that the age of print on paper is far from dead.

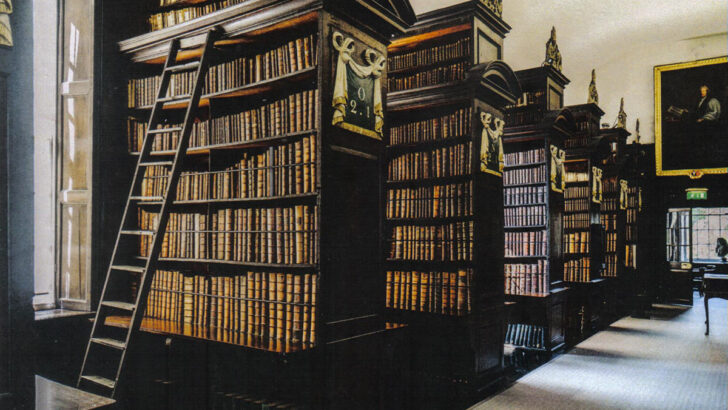

The current exhibition at Marsh’s Library is, for anyone interested in the beginnings of the printed book, quite a delight. Marsh’s Library itself, though seemingly tucked away in an obscure corner of the city behind St Patrick’s Cathedral, is in actuality one of the most visited places in Dublin.

Founded

Marsh’s is the country’s oldest public library, having been founded back in 1701 under special legislation. Its historic collections, which can still be read by those making application in advance, are of immense interest for the rare items they contain.

This catalogue which has just appeared, one of the irregular publications of the library, is a wonderful piece of Irish book design and production. It is full of interesting things for the bibliophile and the historian. It is accompanied by an exhibition of a select number of these earliest examples of the printer’s craft, which everyone can enjoy who has ever wondered about the transition from such manuscript treasures as the Book of Kells into a printed book.

Visitors to Trinity College are often overwhelmed by the extraordinary art of the Book of Kells. The interest of these books in Marsh’s Library is more intellectual than purely artistic.

Many of the books on display reveal their kinship with the western manuscript tradition, for the first printers from Gutenberg in 1450 onwards”

These are 75 exceptionally early books out of a collection that runs to over 26,000 volumes. They are in a way the real treasures at the heart of the library’s collections. As each year passes their importance increases, yet their audience becomes ever more specialised.

Many of the books on display reveal their kinship with the western manuscript tradition, for the first printers from Gutenberg in 1450 onwards simply adapted the make-up of manuscripts as the format of the new printed volumes.

The Italian scholar who has written the catalogue records detailed information on each one, giving the reader indications of the online resources which give far fuller details of the book that would be reasonably possible in a mere catalogue.

There are times though when one’s curiosity is aroused and one would like to have been told more. But what she does have to say underlines just what a literary treasure house Marsh’s Library truly is.

It was not always possible for the early printers to provide their books with illustrations. But some of those on display are quite fascinating. Some are quaint, such as a wood cut from a world chronicle by Werner Rolewinck in 1494, showing the burning of Troy in 1184 BC, showing those “topless towers of Ilium” in flames, alluded to by Marlowe’s devil raising Doctor Faustus about 1592.

Quite charming too is an image of Noah’s Ark again from Rolewinck, (Genesis 8:10-11) anxiously waiting for the return of the dove to the Ark, from which the animals also peer out. This was in 2348 BC, according to Bishop Ussher of Armagh’s famous calculation of the dates of Creation and the Flood.

Remarkable

But the most remarkable is a woodcut of Venice from Breydenbach’s record of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land (printed in 1486). Another picture of his (not illustrated) shows the wild animals of the Holy Land, among, remarkably enough, is a unicorn. I have written about this elsewhere: the unicorn was perhaps not quite the complete creature of fancy as is often supposed today.

The introduction of printing (“invention” is a contested term for some scholars) plays an important part in both the rise of the Reformation, and afterwards the Catholic Counter Reformation. A page from the Roman Index is illustrated, the valiant if useless effort on the part of the Papacy to control the extraordinary explosion of opinions and ideas of all kinds, with a dramatic expansion of printers, booksellers and libraries.

The first item printed in the new font in 1571 was an ‘Irish ballade’ on the Day of Doom written by a Catholic poet”

There are no samples of Irish printing in either the catalogue or the exhibition. The German historian of printing from 1450 onwards, S.H. Steinberg, noted that “in connection with the Elizabethan settlement of the national church, the Irish language was drawn into the orbit of the printing press”.

In or before 1567 Queen Elizabeth I ordered the cutting of a special font of Irish types for editions of the New Testament and the Anglican catechism.” Actually the first item printed in the new font in 1571 was an “Irish ballade” on the Day of Doom written by a Catholic poet.

“As has not infrequently happened with the English government’s activities in the affairs of Ireland,” Steinberg observes tartly, “ the result was very different from the intention.”

Saved

Indeed, it may well be that printing saved the Irish language. The same scholar remarks that the other Celtic language, Cornish, “became extinct for lack of a printed literature”. Thus printing, it seems, lies at the heart of the survival of that essential element of our native identity, our ancient language.

The story of the rise and achievements and accomplishments of printing overall in Ireland is a fascinating one, to which this fascinating book makes a due contribution. Marsh’s Library from time to time mounts exhibitions on aspects of the making and the preservation of books in Ireland well worth looking out for.

The creator of the book, Sara D’Amico, took an MA in Library Science at a university in Rome before going on to the Vatican School of Library Science, founded as recently as 1934, as an indication of the scientific and scholarly developments in that ancient library, famous since the Renaissance for its holdings of Greek and Roman classics, itself an historic library of major importance.

D’Amico is presently working for a PhD at the University of Alicante. In cataloguing the incunables at Marsh’s Library she set herself a neat little problem which had wide reverberations.

(Marsh’s Library, St Patrick’s Close, Dublin 8; Mon.- Fri. 9.30-5; tel. 01- 454 – 3522; tickets, €47.00 (full fee), €4.00 (concession rate); email: informationmarshlibrary.ie.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello The original shelves of Marsh’s library have stood the test of time

The original shelves of Marsh’s library have stood the test of time