Personal Profile

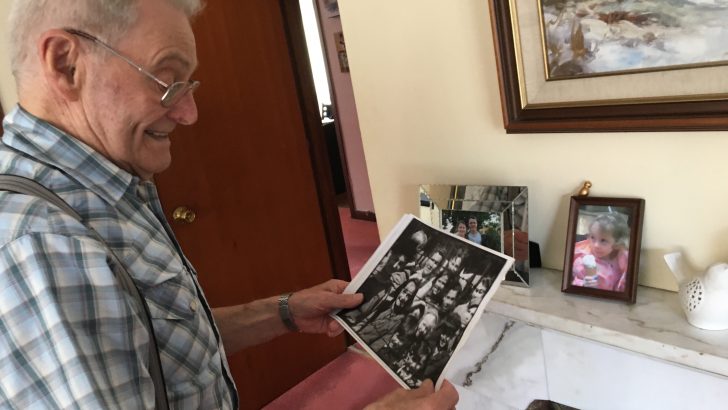

Matthew Carlson speaks with a Holocaust survivor

Tomi Reichental has lived quite a life, even by normal standards. He is an author, public speaker, world traveller and to top it off, is one of the last survivors of one of humanities darkest time, the Holocaust.

Born in Slovakia in 1935, Tomi has pleasant memories of his small village of Merašice. His family had been there for generations, Tomi’s research going as far back as the late 1700’s.

In March of 1939 however, the Nazi regime occupied what was known as Czechoslovakia and established the dictatorship of Jozef Tiso (who also happened to be a Roman Catholic priest) which marked the beginning of propaganda against Jews in what is now Slovakia. Tomi explains that because there was no television or radio in the rural area, the church was the main source of information. “The propaganda was spread through the churches,” says Tomi.

“And of course, because people in the rural area, simple people, they went to church and listened to what the priest said about the Jews, they began to believe it.”

Deportation

The deportation of Jews in Slovakia began in March 1942, but because his father was deemed useful to the economy, his family was given a document that spared them of deportation. However, that didn’t stop the dictatorship from passing laws that oppressed the Jews.

“We had to wear a yellow star, we couldn’t go to public places like the cinema, we couldn’t go to the national school. Suddenly we were ostracised from the Slovakian society,” says Tomi. He recalls that even though his family had been there for generations and assimilated to society, he felt like a stranger in his own home.

An uprising against the government in August of 1944 sparked the deportation of the rest of the Jews, no document keeping them safe. Tomi recalls that his father was taken separately, Tomi not knowing if they would ever see him again. Tomi and 35 members of his family were caught on October 16 and on November 2, 1944 he along with his mother, brother, cousin, aunt and grandmother arrived at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Tomi and his family were kept in the women’s half of the camp, separated from the men. “My recollection from the camp is that the only way to describe it is ‘hell on earth’. The people that we saw when we arrived were just skeletons walking around,” says Tomi.

He told of how he often saw the women fall to the ground due to starvation or sickness. “They were weak and malnourished and cold and we would stop playing to wait and see if she got up. If she got up we said ‘great, she will live another day’, but most times they didn’t get up. They died where they fell,” says Tomi. He said that these were the kinds of horrors that became a part of everyday life at Bergen-Belsen.

In January of 1945, prisoners from Auschwitz concentration camp were transferred to Bergin Belsen due to the German army retreating. This brought the population of Bergen-Belsen from 25,000 to just over 60,000. This congestion increased the spread of typhoid, killing approximately 500 people a day in the months of February and March.

“I remember that we used to have a kind of green area in the camp where the children would play and chase and play hide-and-seek, but we didn’t hide behind trees or walls, but behind piles of corpses,” said Tomi. But the news of the German army retreating brought hope to the prisoners of the camp that freedom might be near.

On the afternoon of April 15, 1945, Tomi remembers a rumbling sound. Rushing to the gate, squeezing to get a glimpse of what the noise was, he recalls hearing: “This is the British army, you are being liberated!” Two and a half months later, Tomi and his family were reunited with their father (who escaped and joined the resistance army) in Merašice.

Tomi’s return to normality wasn’t immediate however. He hadn’t attended school for four years. “I was 10 years old, nearly 11, and I had to sit with six or seven-year-olds because I couldn’t read or write or do mathematics, I had to start from the base,” says Tomi. “It took me two years of lots of studying to get back to my age.”

Tomi ended up attending university in Germany of all places and becoming a qualified diploma engineer. Tomi says that a long story short, his cousin got him a job starting a zip manufacturer factory in Ireland, met a Jewish girl and got married. “My wife passed away in 2003 and so I thought ‘Why am I still working?’ so I retired,” says Tomi. That made him reflect that as one of the last survivors of this horrific thing, he should speak out about it.

For the first time in 55 years, Tomi began to speak about the time spent in Bergen-Belsen. “I never told anybody about it, not even my wife or children knew. Everybody was shocked,” says Tomi. Since then, he has written a book about his time in the concentration camp as well as helped make three documentary films and continues to tell his story in schools and universities, fighting the racism, xenophobia and hatred that affected him so deeply.

It is clear though, that even in the midst of a great tragedy and great pain, Tomi has been able to impact the lives of thousands of people who have heard his story, which will be his legacy.

Tomi reminiscing over

a picture capturing the liberation of Bergen-Belsen.

Tomi reminiscing over

a picture capturing the liberation of Bergen-Belsen.