Vital symbols of Ireland’s Catholic heritage are in danger of being lost, writes Susan Gately

For over 60 years in the late 17th and early 18th Century Catholics in Ireland were severely persecuted under laws which effectively took away their rights to property, education, participation in civic life and most importantly, religion.

Officially termed Laws in Ireland for the Suppression of Popery, the penal laws were described in the following terms by the 19th-Century historian Edgar Sanderson: “A ‘Papist’ could not be a guardian to any child, nor hold land, nor possess arms. No Catholic could hold any office of honour or emolument in the state…or vote for members of the Commons. It was a felony, with transportation, to teach the Catholic religion, and treason, as a capital offence, to convert a Protestant to the Catholic faith.”

Writing in 1792, the Dublin-born Edmund Burke, then an MP for Malton in Yorkshire, described the laws as “a machine as well fitted for the oppression, impoverishment, and degradation of a people…as ever proceeded from the perverted ingenuity of man”.

Confessions

In spite of this, Catholics continued to practise their Faith. Chapels were established in the backstreets of towns, while in rural areas, Catholics met in the open air at ‘Mass rocks’. Priests who were hunted would travel from Mass rock to Mass rock, hearing Confessions, baptising, performing marriages, and most importantly, saying Mass.

It is believed that there are hundreds if not thousands of Mass rocks strewn all over the island of Ireland but according to Dr Hilary Bishop there is a real danger that the locations of many are being lost. This, she says, is shocking.

“They are the symbol of Catholic heritage. They are what kept the Faith alive throughout the penal era. If Gaelic communities hadn’t gone to the Mass rocks, the Faith would have died out. That’s what kept Catholicism alive.”

Human geographer Dr Bishop, from Northwest England, came to her studies of Mass rocks by chance. For years she worked in finance but when she was made redundant, she began a course in Irish studies at the University of Liverpool.

As she walked the fields talking to Irish farmers for a research Masters she began to hear about Mass rocks: “Nobody was really looking at them to any degree.” From this grew her doctoral research project on Mass rocks in Co. Cork.

Within the Archaeological Survey Database (ASD) of the National Monuments Service for Ireland, Mass rocks are classified as “a rock or earthfast boulder used as an altar, or a stone-built altar used when Mass was being celebrated during Penal times (1690s to 1750s AD), though there are some examples which appear to have been used during the Cromwellian period (1650s AD)”.

The ASD records the locations of some, but in practise many are not recorded. “A lot of Catholic sites were not put on maps when the maps were originally done as it would have legitimised the Catholic faith to have included them on the maps,” explains Dr Bishop.

For example, the ASD listed 100 Mass rock locations in Cork, but Dr Bishop found over 400. It is a complex situation, she says. Often there can be several records of Mass rocks in the same townland with different names – they can either be multiple entries of the same site or different Mass rocks in the same area.

“If one site was discovered or became unsafe, they would have gone to worship at a different site at a different location,” she explains.

By definition the Mass rocks were often located in obscure, hard-to-find places, many of which are now overgrown.

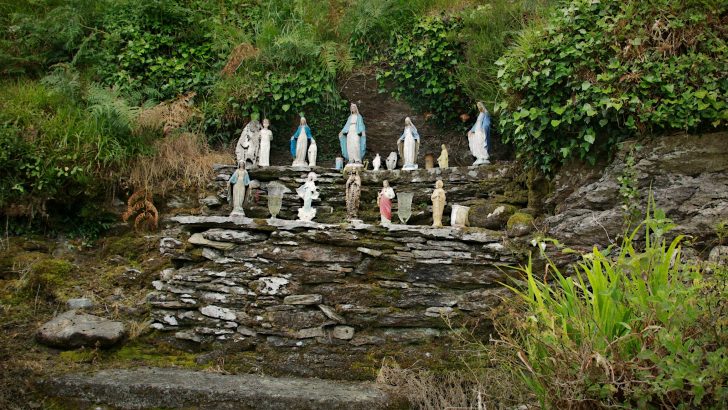

According to Dr Bishop, most have certain features: they are close to water – important for the ritual of Mass and also to hide the footprints; they are often a “special rock” – something unique within the landscape. In addition they will have a ledge about a metre high – for the altar, perhaps a windbreak and a ‘reredos’ where they could put a statue. Some have an engraved cross.

But even if you find a stone like this, it is not necessarily a Mass rock. There has to be independent verification.

“There would have to be some heritage attached to it, some form of information passed down through the families like: ‘Don’t plough there, be careful, because that’s a Mass rock’,” she explains.

Information

For Dr Bishop, her starting point is usually the Schools Manuscript Collection in UCD. This project from the 1930s involved asking children to go home and collect information from their parents and grandparents about their local areas, including Mass rocks.

However since then, she fears much knowledge about Mass rocks has been lost. “I suppose there comes a point where certain generations are less interested in the sites and less interested in their religion and their heritage.” If the information is not passed on, the knowledge of the Mass rock is gone.

In addition, the rocks seem to have fallen through a gap in heritage conservation.

“The penal laws were 1695 to 1756 – though I’d argue they go back to Elizabethan times,” she says. “Most archaeological monuments are pre-1700. For archaeologists they are ‘too modern’, for historians they are ‘archaeology’.” Mass rocks recorded as Historic Monuments gain some legislative protection but most are not protected.

The findings of Dr Bishop’s research in Cork, Galway, Mayo and Tyrone are on her website: www.findamassrock.com. She appeals to the public for help to find and record many more Mass rocks so that this vital piece of Irish heritage will not be lost. “The website is expected to be a two-way exchange. If people can let me have information about the Mass rocks they know of – photographs, co-ordinates (if it is not on private land), how they know it is a Mass rock and stories associated with it, I can put that on the website.”

The more information she has, the more “armour” she has to “do battle on the grant funding side” so the sites can be properly recorded and visited. “They are important. I don’t want them to be lost and forgotten.”

Susan Gately

Susan Gately A stone-built altar used for Mass

A stone-built altar used for Mass