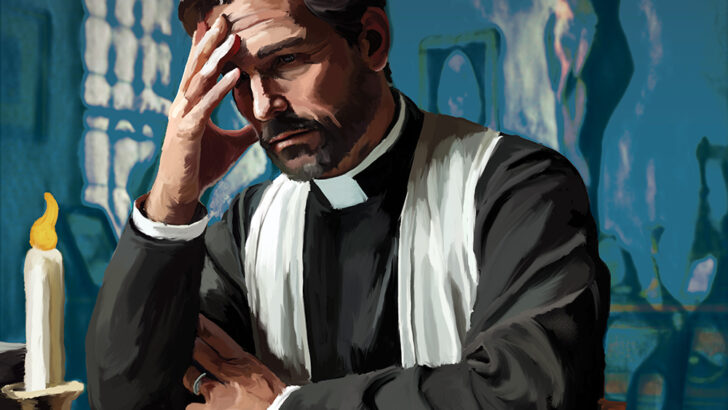

Relentless Ministry – In a new series written by Priests, we will explore what most priests describe as “Relentless Ministry” and the challenges of being a priest in Ireland today

Speaking to priests recently, the key take-away is how busy they all are. In one group of priests– a quick survey showed– none of them had had a day off in six weeks! Another told me he had 17 funerals in four weeks. Shocked, I spoke to more priests who didn’t think 17 funerals in a month was anything special! I began to realise that the further I dug, the crazier it was getting. One priest encapsulated it when he referred to it as ‘Relentless Ministry’. He said: “The Irish are innately spiritual, just look at the amazing response to the relics touring the country recently, faith is alive. But the model we are pushing is dead.”

It is with something approaching incredulity that many priests that I speak with react when they hear fresh news of the Church in Ireland’s ‘synodal pathway’. In many cases, a pleased incredulity to be sure, but anyone could be forgiven for a certain level of fatigue. Even the bishops in their Winter Meeting statement admit it.

For many, Pope Francis is asking us to play senior hurling, while we struggle to pull together a reserve team. Most priests in most parishes are at full stretch, and then some.

Workload

Even where priests are enthusiastic about synodality, [don’t get me wrong, as a lay person I was an early enthusiast] the daily dose of funerals, weddings, baptisms, sick calls, safeguarding training, GDPR forms, music rights checklists, heating bills, insurance requirements, cemeteries, schools, diocesan committees, special collections, leaves little time for what some view as ‘blue sky’ thinking about the Church of the future.

Add to the daily grind, the need to cultivate an authentic spirituality of ministry, and most priests will admit that they are struggling.

Many priests are in serious danger of ‘burn out’, while some will openly admit that they often feel bullied by the unrealistic demands”

To be clear, most priests are happy in their ministry – but many feel entirely unsupported by their superiors, especially as the work load grows. Most bishops are motivated by genuine feelings of goodwill for their priests’ welfare, but there is a subtle ‘don’t ask/don’t tell’ when it comes to issues like the need to get at least one day off every week, or annual leave entitlements. Priests are responsible for arranging their own cover, and the truth is that there is no spare capacity in the system. Cover invariably means asking the busy priest in the neighbouring parish to keep an eye on the welfare of the souls entrusted to you, as well as his own.

And this is not about beating up on the bishops, most of them have been in parishes and understand only too well the vicissitudes of priestly life. But I do think it is fair to say that the Church as an institution does have a culture of washing its hands of problems, or burying its head if you prefer. It doesn’t make people bad, but it is bad management and bishops are essentially managers to their priests.

Many priests are in serious danger of ‘burn out’, while some will openly admit that they often feel bullied by the unrealistic demands of people, many of whom are parishioners in name only and rarely if ever attend Mass, and certainly don’t financially support the parish. These are often the loudest and most demanding, the ones that will be on Joe Duffy’s Liveline when a church finally closes because there’s no priests and no money and few parishioners to keep it going. They want and demand a Church that they knew 40 years ago, that is going or gone. Those people should be ignored.

Priority

Most priests are naturally inclined to be people-pleasers, and that’s no bad thing per se. But, this tendency to ‘meet people where they are at’ can often lead to a priest being treated as a doormat, or giving up his day off to please a parishioner who wants a particular anniversary Mass said on a particular day to suit a grown-up child who is home from Australia, and has never seen the inside of a church in the sunnier reaches of the southern hemisphere.

The incredulity – as I say, often a pleased incredulity – is the growing realisation among many priests that the ‘synodal pathway’ however visionary and future-looking is not addressing the urgent here-and-now issues. Take the current church infrastructure in parishes for example. Will some churches have to be closed? Yes, it’s a no-brainer. Which? Where? According to what criteria? Do we close remote country churches, or the ill-attended cavernous churches where people have long since gone to the Tesco superstore for their bread and wine?

Their hearts are full with the hopes and disappointments of their people, whom they love dearly and serve with devotion”

Like most priests and laypeople, we long for a Church that is more participatory and where everyone feels at home and feels both listened to and understood. But all the patient discernment in the world will not change the reality that we are fast running out of priests, and without priests we do not have the Eucharist, and without the Eucharist, according to Pope Benedict XVI, we do not have a Church.

There is also the fact that many priests feel mildly chided by the fresh emphasis on synodality, as if they have not spent decades listening to the joys and sorrows of their people. Any priest will tell you, that their hearts are full with the hopes and disappointments of their people, whom they love dearly and serve with devotion. And all the while, there is always that parishioner whose opening greeting to the priest is always “Father, do you know what you should do?” as if the path to renewal is easy to follow, and the priest just hasn’t embraced it.

If we’re honest, too, how many of our parishes are brimming with people willing to help ease the burden of priests? How many families, even if they are not church-going, will allow a local lay leader preside at a funeral liturgy or bury a loved one? Anecdotally, priests will tell you that some parishioners are unhappy if the funeral is presided over by a non-Irish priest, where then will come the appetite for the necessary lay-led liturgies?

Compensation

And the elephant in the room, priests are badly paid and are unlikely to be getting minimum wage for the hours they work. Funerals and weddings supplement a meagre wage; if these are reduced or taken away by laity, will the priest be compensated for loss of much needed income? Priests won’t talk about money but they have to live and are entitled to be treated justly. The Church is great at pointing outwards when it comes to social justice, but its internal checks and balances leave a lot to be desired.

It’s easier to plan for some imagined future than face the seemingly intractable challenges present in our reality”

Synodality, if it is to be more than an academic exercise or a process that will take decades, it must address the pressing challenges facing the Church in Ireland today, in every parish in the country. One priest I know replaces the word ‘Synodality’ with ‘Conversations’. The need for careful deliberation is piercing, but so too is the urgency of the situation and we really, really need to talk about it. There is no point in planning the Church of the 22nd Century, when the one in the here and now is in a deep structural crisis. But it’s human nature – it’s easier to plan for some imagined future than face the seemingly intractable challenges present in our reality.