Despite setbacks at the ballot box, the Church must not lose its nerve, writes David Quinn

Back in the 1990s, Ruairi Quinn, then Finance Minister, declared Ireland was now ‘post-Catholic’. He said it in the aftermath of the 1995 divorce referendum. He knew that many people still went to Mass. What he meant was that even then we lived in an Ireland where the political influence of the Church no longer really existed.

If we were not post-Catholic then, we certainly are now. The repeal of the Eighth Amendment by a two-to-one margin last May was momentous, but in a way, it was also simply a cleaning away one of the last major influences of Catholicism on Irish law.

The Eighth Amendment was never a purely Catholic law, of course. It was supported by people of other faiths and none, and in Northern Ireland, Protestants provide more political protection for the pro-life law there than the ostensibly ‘Catholic’, or nationalist parties.

Popular culture

Nonetheless, in our particular cultural and social setting, the Eighth Amendment was very much a product of Catholic Ireland. With the Eighth Amendment out of the way, the major change sought by secular campaigners is to our schools. Many so-called Catholic schools are really that in name only at this stage, but don’t be surprised if calls soon grow for a referendum to nationalise all the Church-run schools in the country.

In this sort of a setting, where the social and political influence of Catholicism is small, religious practice is diminishing, and there is huge hostility towards the Church, what should our stance be vis a vis society?

The temptation is to keep the head down. As I wrote last week, a lot of Catholics have learnt to be quiet, in the same way people of Anglo-Irish descent learnt to be quiet in the first decades after independence, prompting WB Yeats to famously tell the Seanad, “We are no petty people,” and defend his Anglo-Protestant heritage in an often very hostile climate.

An accompanying temptation will be to concentrate on the pastoral side of the Church’s mission only, that is, the charitable outreach to the poor, the lonely, the hungry, the afflicted.

In a way, the Church has been concentrating on the pastoral side for several decades now at the expense of evangelisation and its prophetic witness.

Until very recently, the Church hasn’t really needed to evangelise, because social norms did that for it. We grew up in a country steeped in (a version of) Christian values and beliefs and these were passed on by a sort of osmosis, even if a lot of the time the piety was outward only and the Church became a willing instrument of imposing ‘respectability’ upon people.

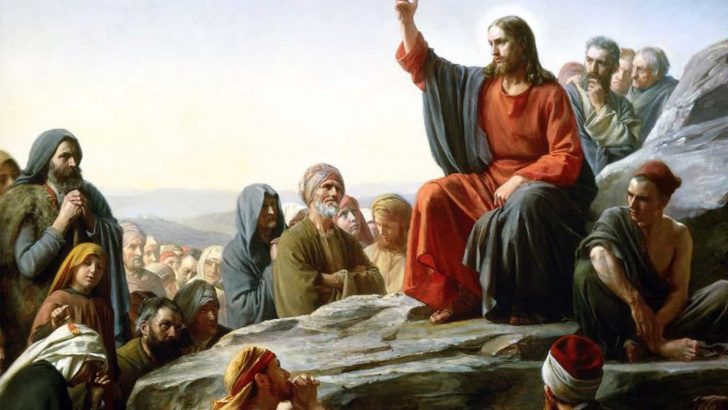

But now we do need to evangelise, that is, to convince people of the truth of the Gospel and to persuade people that a life of Christian discipleship is better than every alternative. That is not easy to do in a country that thinks it knows what Christianity is, and in which relativism prevails and therefore the claim that Jesus is the Way, the Truth and the Life, rather than a way, a truth and a life, is deemed offensive.

Pope Benedict once referred to the ‘Dictatorship of Relativism’, and by this he meant the insistence that no overarching truth claims can be publicly advanced, except paradoxically, the claim that there is no Truth.

Rather than evangelise, the Church really just muddles along, hoping that ‘cradle Catholics’ will grow up to become practising Catholics, which rarely happens anymore because the social norms are pushing younger people out of the Church, not drawing them in.

And unfortunately, pastoral work only is no substitute for evangelisation. If it was, the churches would be full again.

Lots of priests, religious and laypeople do fantastic pastoral work but this is not reconverting society. Pastoral work must be done for its own sake, obviously, but it can’t be confused with evangelisation.

The other thing that gets deemphasised when we end up over-relying on a pastoral approach is the Church’s prophetic mission. Following the line of least resistance is extremely tempting.

But the job of the prophet is to speak out against principalities and powers when need be, and to speak out against public opinion when that is required.

That is extremely unpopular work (by definition) and sometimes risky as well.

Aspects of the Church’s message run very much against the modern grain, especially when its message relates to sexual morality, but also to anything that seems to deny people their personal choices, including assisted suicide. Demand for this is going to grow as our population ages.

But an extremely individualistic, relativistic culture needs to be challenged. We mustn’t lose our nerve.

For one thing, a hyper-individualistic society needs to be challenged in principle, but secondly, it needs to be challenged because it is creating so much human misery.

Mission

So, the Church must be pastoral certainly. But it must be evangelistic as well, and prophetic. Not everyone is called to do all these things, but all of them form the mission of the Church, and we must carry out whatever aspects of the Church’s overall mission are best suited to our own individual talents. We need pastors, but we also need evangelists and prophets.

David Quinn

David Quinn