Revolutionary: Who Was Jesus? Why Does He Still Matter?

edited by Tom Holland (SPCK Publishing), £19.99 / €23.99

It is a very popular question today to ask ‘who is X’? The answer expected is one that must, in a few short sentences, sum-up exactly who X is. That is an ambitious target, so to add on a second question – why does X still matter? – is setting quite a task.

It is one which Revolutionary: Who Was Jesus? Why Does He Still Matter? never manages to complete, with honourable exceptions, including former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams’ concluding essay.

The book is a collection of essays, nine in total, by a variety of contributors from different faiths and perspectives. The editor Tom Holland has quite a following in Christian circles, being an inventive popular historian and author of Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind or How Christianity Shaped the West.

He returns in this collection to a beloved theme of his: the ways in which the Christian revolution shapes our conception of the world two millennia after the death of its founder. Here, his focus is on the revolutionary nature of Christ’s life and death, and the following he garnered.

Heterogeneity

The immediate problem the book runs up against is the heterogeneity of its authors. This is a deliberate choice, but it results in a book that is quirky and contrarian, without ever making much sense. Jewish, Muslim, atheist and Christian scholars and journalists rub shoulders. Each contributor has the opportunity to elaborate their own pet theory about Christ’s revolutionary character. Unfortunately, as with most pets, these are irrational creatures and prone to biting their master’s hand.

For instance, it’s hard to grasp how Jesus can be considered revolutionary when you believe he never even existed; and yet this is Julian Baginni’s view. It’s also understandable that you wouldn’t consider Jesus especially revolutionary when you don’t think he is the son of God; this view can be attributed to a number of the authors. From that starting point, most contributors render themselves redundant or at best curiosities.

But there is some interest in the book, mostly from quarters you would expect. The essay of the greatest subtlety is Rowan Williams’, which follows on from Baginni’s confused view of Christ as an imaginary figure, revolutionary in his ambiguity and the impossibility of explaining what any of his teachings mean.

Reception

Williams’ approach is phenomenological and narrative based, attempting to explain how and what the Gospels teach us about the reception of Christ’s life and teachings. Williams explains that a tradition gradually developed among followers, which quickly agreed on a number of issues, including Christ’s divine origins. It also established the areas of debate, such as the scope of his invitation to be Children of God – Gentiles as well as Jews are invited.

The ambiguity Baginni praises Christ for only exists if you consider biblical sources as all that we know about Christ’s life; but these are a part of the Christian tradition, not its sum.

The other interesting sections are those written by, as it were, actual theologians. The Islamic perspective on Christ, taking a chronological approach to his reception in the Muslim faith, was very illuminating. It was well laid out and educational, suggesting that the author – Tarif Khalidi – is a man of great learning, and skilful in conveying what he knows.

In all, however, the book fails to answer the questions it asks; in what way was Jesus revolutionary? The only certain answer you come away with is that it is unlikely to be in the manner described by the authors of these essays – with honourable exceptions.

Ruadhán Jones

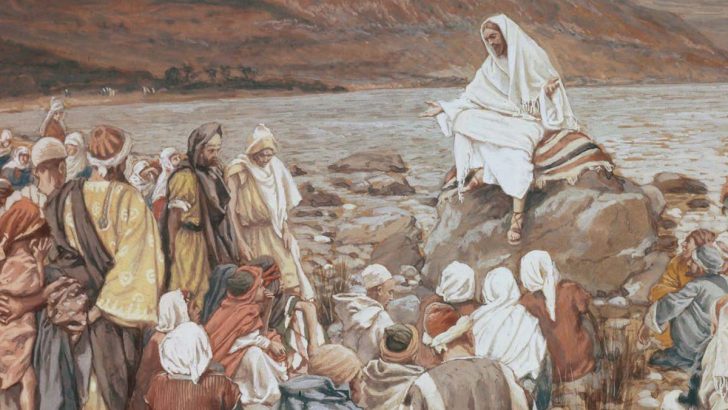

Ruadhán Jones Jesus preaching to the people by the Sea of Galilee, painting by J. J. Tissot

Jesus preaching to the people by the Sea of Galilee, painting by J. J. Tissot