The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis

by Alan Jacobs (Oxford University Press, £20.00)

Frank Litton

“Every age has its own outlook. It is generally good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes.” We, therefore, need books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means old books.’

So wrote C.S. Lewis in the 1940s when the ‘characteristic mistakes’ of the age had devastating consequences, and the need to find a perspective that would bring them into focus was urgent.

What were the cultural defects that allowed the seeds of war to grow and thrive? What reformations in our culture and politics would secure a better, more humane post-war world?

C.S. Lewis was not the only prominent Christian thinker raising these questions and seeking answers. This elegant book examines his efforts along with those of W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot, Jacques Maritain and Simone Weil.

There were substantial differences in how each responded to the challenges of their times. Jacob traces these while keeping what united them in view; a difficult task that he accomplishes with aplomb.

They shared the assumption that the times challenged the Christian; that the Enlightenment took the wrong turn; that the thought of ancient Greece was an essential ‘old book’.

Approaches

Not surprisingly the approaches of Maritain and Weil had a stronger philosophical inflection than those of Auden, Eliot and Lewis. While all were attentive to culture and cultural critique, Maritain and Weil paid more attention to politics.

Though all are still in print, they have receded from the public view. Having read Jacob’s lucid account of their thinking, the reader is likely to regret this. Both the seriousness and scope of their enquiries surpass what today has to offer the general reader.

For instance education was a central concern. All would have agreed, in their own way, with Maritain when he wrote “the prime goal of education is the conquest of internal and spiritual freedom to be achieved by the individual person or in other words, his liberation through knowledge and wisdom, good will and love”.

We live in a simpler world where our educators have little more to offer than training in the importance of consent in the face of the complexities of human sexuality and personal relationships; it is hardly a better world.

The relationships between Christianity and politics, and Christianity and culture preoccupied our thinkers. While Christianity could not, should not be subsumed into a political programme nor reduced to a cultural expression, they believed it had a vital contribution to make to both. Indeed, Maritain’s Christian-inspired understanding of human rights made a substantial contribution to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Marriage

Simone Weil was maybe an exception. She was an outlier in the group. While the others found inspiration in the culture and philosophy of the middle ages, she did not. She deplored the marriage of religion and politics which brought power (force) into alliance with Christianity. This, not the Enlightenment with all its failings, was the fatal wrong turn.

Jacques Ellul paints a picture of the culture that came to dominate the post-war, western, world. With its emphasis on technique it knows only means and has nothing to say about ends. It cannot ask, still less answer, the questions about what excellencies we might aspire to and what obstacles might impede us, the concern of our thinkers.

It replaces discussion of ideas of the good with talk of values. Jacob reminds us of Ellul’s analysis, and asks was all the work and thinking he so competently reported in vain?

The relationships between Christianity and politics, Christianity and culture preoccupied our thinkers”

We hear increasing talk of the “30 glorious years” that followed the end of World War II that brought us prosperity, peace, the welfare state, the EEC. Christian democracy, informed by the ideas discussed in this book, made a substantial contribution to this achievement.

That was yesterday; today we having rising inequalities, fragile democracies, drastic climate change, a weakened European Union and an unmanageable globalisation.

This book with its discussion of the recourse to “old books” helps us find a perspective on the “characteristic mistakes of our age”. I reckon that we have most to learn from Simone Weil with her reminder of the radical demands of the Gospels and the dangers of the thirst for power.

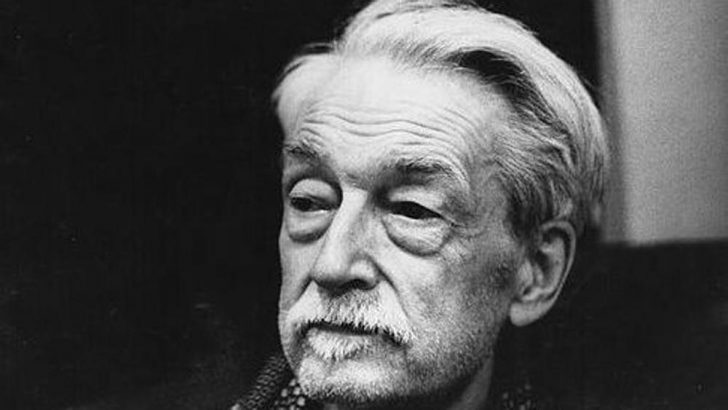

Jacques Maritain

Jacques Maritain