Patrick Ussher

Through the pain and suffering of hardship and illness, there can emerge a beam of light. Over time, that light can become increasingly brighter until, eventually, it can illuminate your life in a wholly new way. Illness does not have to define us. We can be ill, yet whole.

When I was a child, I asked my mother, Mary Redmond, what the meaning of life was. She answered: “To Live, To Love and to Leave a Legacy,” words of advice that her father had also given to her when she was young.

Her legacy has been far-reaching and includes her extensive legal and academic work in employment law. In early 2018, a new edition of one of her legal works was updated by Dr Desmond Ryan and published, in tribute to my mother, as Redmond on Dismissal (Bloomsbury). Outside of her legal work, my mother was actively involved in the charity sector in Ireland. In 1999, she instigated a national charity called The Wheel, which brings together the community and voluntary sectors. The Wheel has promoted the idea of ‘active citizenship’ and has played a key role in encouraging a more participatory democracy in Ireland.

But her father’s advice to her ultimately led my mother to fulfil another far-reaching aspect of her legacy and from the most personal possible circumstances. Indeed, it was the careful and kind hospice care that her father, Sean Redmond, received at the end of his life which led my mother to found, in 1986, The Irish Hospice Foundation, a charity which campaigns for best practice at end of life care.

Hospice care

The Irish Hospice Foundation has played a huge role in bringing hospice care forward in Ireland over the last three decades. In 1986, there were only three hospices in Ireland, today there are nine. Whereas then only one specific area in Dublin had access to hospice home care services, now this is a national service which anyone at end of life can avail of. My mother’s work in The Irish Hospice Foundation was part of a dream, a vision, that no one in Ireland should go without dignified end of life care. My mother had a special capacity to envision change. As she once said: “As anyone with a dream will tell you, not only does it never go away, you see it, you can touch it and you talk about it at every opportunity.”

Those achievements represent the core of my mother’s legacy and, in 2014, she received an honorary doctorate from Trinity College Dublin for these contributions. As her son, however, I witnessed what was, for me, a different kind of legacy and a much more personal one. And that legacy came from how she lived and how she loved, those two other aspects of her father’s advice, over the six years of her breast cancer. Over those years up until her passing in April 2015, I saw her truly live to the fullest. Not in the sense of packing a whirlwind of activities into every day but rather by living out fully the ‘quiet miracle of the ordinary’.

I could see clearly how a sense of the deep preciousness of each moment took root in my mother, despite the physical pain of illness. As she wrote: “Help me to accept my everyday / just as it is, / the quirky pains and aches all over, / tenderness in hands and feet. / This, my everyday / I lay before you as it is.”

Acceptance

This acceptance freed her heart, allowing it not just to accept, but to love, her everyday. It also allowed her to be fully present in sharing a cup of tea with a loved one, in taking in the sunlight of spring, in gardening and in painting. And, most strikingly, this acceptance freed her to be fully present for friends and family, to be the kind and listening ear, to leave others feeling better than before they met her, and to be a loving sister, wife and mum.

My mother called the strength to live in this way the ‘Pink Ribbon Path’, and it stemmed from her own experience, from her practice of meditation and from a wide range of inspiring authors whom she read in the early years of her illness. After some years, she drew together her own writings and these different sources of inspiration and, in 2013, the Pink Ribbon Path was first published under my mother’s married name, Ussher.

My mother passed away, surrounded by family, on April 6, 2015. Two days before that, I had my last conversation with her. On that day, I told her how beautifully she had walked the Pink Ribbon Path, and I promised her that I would do my best to ensure that it would live on, which is why we have published a revised version of the book called Following the Pink Ribbon Path.

“Today more than any other day I see myself taking up the Cross of Christ and carrying it. I will do so with a smile.” – June 10, 2009.

These words, written by my mother on her first day of chemotherapy, became symbolic of how she came to live in the years that followed. I will never forget how intensely beautiful and radiant her smile remained, often in the face of great suffering.

Early into her treatment, I remember her learning to smile at the grey, wispy hairs that had started to grow on her head and, later, proudly displaying her new ‘hair-style’, something that entailed being in the world with great vulnerability. For me, that new hair-style, in time, became the most beautiful hair, representing the inherent strength that living with vulnerability necessarily involves.

That vulnerability also focuses the mind on what really matters though, and that is the very business of living and the quiet miracle of the everyday. Early on, my mother made a decision not to “participate in her illness”. By this she meant that she decided not to let the ‘narrative of illness’ take over her life, choosing not to get caught up in a reality where ‘being sick’ was the predominant output. Instead, she wrote to herself: “Decide to fill your world with joy. Anticipate joyful events each day and ponder them in the evening.”

This is not to deny the reality of illness or the need for careful consideration of treatment and management of symptoms. Rather, this is about making the conscious decision that our daily lives need not, as far as we are able, be weighed down by the burden of illness.

That this was possible was also because she surrendered to God. She wrote: “When a diagnosis of serious illness arrives, we are challenged in what we believe. God’s face seems hidden. As a lawyer, I was used to solving problems no matter how difficult. This was a problem I knew I could not solve. And so I placed my hands in God’s. It was ‘over to Him’.”

To leave all in God’s hands relieves us of a large psychological burden, that of trying to solve what we cannot solve, and frees us to focus on positivity and on love, both of which are key. This way of approaching life also still allows for playfulness and humour. Illness cannot deny the right of both to be in our lives.

Early on in my mother’s treatment, she came across an anonymous poem in the oratory of the hospital. It was called ‘The Tandem Bike Ride’:

‘…it seemed as though life was rather like a bike ride,

but it was a tandem bike,

and I noticed that Christ

was in the back helping me pedal.

I don’t know just when it was

That he suggested we change places,

But life has not been the same since.’

My mother said of this poem: “I found exactly that happening to me, that at a certain stage, particularly when I felt I have no answers to this anymore, somehow, imperceptibly, I changed places in the same way.”

Illness can teach us to let go of trying to control our lives and instead let the Spirit guide us, and this can take us to places we would never otherwise have gone.

Following the Pink Ribbon Path by Mary Redmond Ussher is published by Columba Books (€14.99, www.columbabooks.com). Royalties go to the Irish Hospice Foundation.

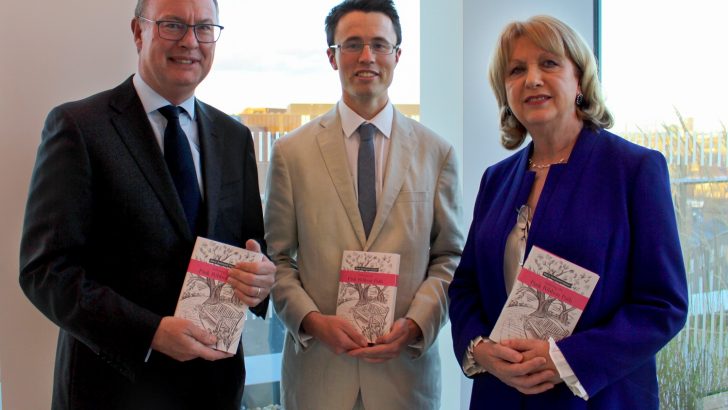

Connor McDonnell, partner with Arthur Cox (launch hosts), Patrick Ussher and former President Mary McAleese at the launch of Following the Pink Ribbon Path. Photo: Alba Esteban

Connor McDonnell, partner with Arthur Cox (launch hosts), Patrick Ussher and former President Mary McAleese at the launch of Following the Pink Ribbon Path. Photo: Alba Esteban