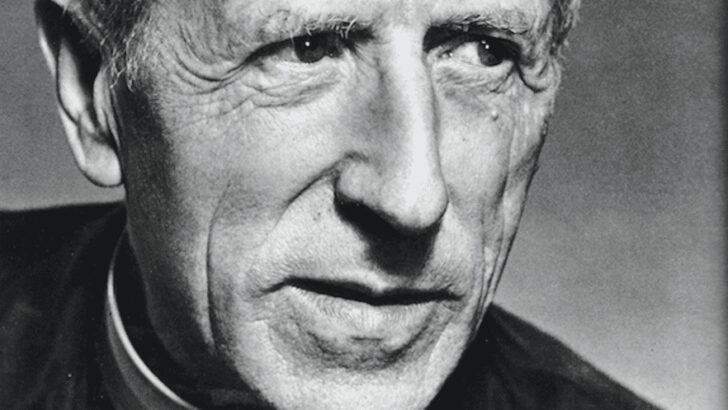

Mark Patrick Hederman explores the life and legacy of the Jesuit scientist/theologian

In a nutshell I would describe him as ‘a mystic in a mouse trap.’

I would rank him with Gerard Manley Hopkins [also a Jesuit] as a poet who has left us with several beautiful thought-provoking images: treatises on the Eucharist, on the evolutionary process, on contemplation, on the Mass and on prayer. I find his writings inspiring and helpful, not as dogmatic truths but as prayerful meditations and striking poems, taking T.S.Eliot’s definition of poetry as ‘raids on the inarticulate’ or evocative ‘stabs at the truth.’

I do not take him too seriously either as a scientist or as a theologian where his theses have been found wanting by experts in both of these areas. When I find current spiritual writers using him as an authority in their offerings, as the medieval writers might have quoted Aristotle or the Pseudo-Dionysus, I tend to close such books and move on to less bombastic and more humble screeds.

Context

Above all, I think we have to situate Teilhard in his socio-historical context. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (May 1 1881 – April 10 1955). You could say he lived at an awkward time and in a personally privileged set of circumstances. He came from a large well-off Catholic family in France, which makes a great difference to one’s educational prospects and self-esteem. His was a minorly aristocratic milieu in a country where Catholicism had established itself as the ruling ethos.

His mother was a great-grandniece of Voltaire. He inherited the double surname from his father, who was descended on the Teilhard side from an ancient family of magistrates ennobled under Louis XVIII.

He was educated by the Jesuits and entered their society as a teenager. He was a gifted scientist who was trained as a palaeontologist with the usual dedication, expertise and flair we associate with training of candidates to that order. Being a priest meant that he studied theology and lived the life of an ordained minister which allowed him to combine two areas of specialisation, theology and science, unusual at the time.

Most Catholics, along with the general public, were outraged at the suggestion that we were directly descended from apes”

Early in his life in the 1920s or so, he made a total commitment to the evolutionary process, described by Darwin, as the core of his spirituality, at a time when other religious thinkers felt evolutionary thinking challenged the structure of conventional Christian faith. Both Darwin and Freud were suspect in most schools of Christian spirituality and theological investigation. We only have to think of the Scopes Trial in the USA, also known as the Scopes Monkey Trial, which was the 1925 prosecution of science teacher John Scopes for teaching evolution in a Tennessee public school, which a recent bill had made illegal.

Most Catholics, along with the general public, were outraged at the suggestion that we were directly descended from apes.

Teilhard developed an evolutionary vision of our planetary future, currently developing from a sphere of life, or biosphere towards a sphere of mind, or noosphere. As a visionary, Teilhard was not only on the brink of formulating what later became the internet, but he also anticipated current academic efforts to understand globalisation, as well as human, cultural and technological evolution.

In 1941, Teilhard submitted to Rome his most important work, Le Phénomène Humain. By 1947, Rome forbade him to write or teach on philosophical subjects.

Such prohibition was no small part of his later sensational publicity. As in Ireland, where authors like Edna O’Brien and John McGahern probably owed some of their phenomenal book sales to the notoriety of being condemned under our censorship act [in the all-female secondary school attended by my sister in the 1950s the girls in her class derived their private reading list from books banned by the Catholic Church – each girl was required, by order of her peer group contemporaries to bring back to school after the summer holidays at least one such banned book to complete the illicit library which was housed under the floorboards of one of the dormitories].

Condemned

In 1962 the CDF condemned several of Teilhard’s works based on their alleged ambiguities and doctrinal errors. Most of this was an attempt to protect the account of the origins of the human race as given in the Book of Genesis in the Bible. As with many fundamentalists today, the word of God as printed in the Bible was that ‘scientific’ account of how the creator had actually fashioned the universe.

Meanwhile, Teilhard was permitted to head for China where he worked on various paleontological discoveries which kept him away from controversy.

Allen Grim [of the Yale Forum on Religion] has said: “I think you have to distinguish between the hundreds of papers that Teilhard wrote in a purely scientific vein, about which there is no controversy. In fact, the papers made him one of the top two or three geologists of the Asian continent. So this man knew what science was. What he’s doing in The Phenomenon and most of the popular essays that have made him controversial is working pretty much alone to try to synthesise what he’s learned about through scientific discovery – more than with scientific method – what scientific discoveries tell us about the nature of ultimate reality.”

It is almost as if having discovered the jawbone of an ass out in the desert, the poet and the mystic in Teilhard began to fashion a complete anatomy of the human race and then to attach this to the magnificent vision of an Omega point towards which we were all evolving and which would be the ultimate figure of Jesus Christ in his risen form where all would be recapitulated. These writings were controversial to some scientists because Teilhard combined theology and metaphysics with science, and they were even more controversial to some religious leaders for the same reason. But the vision is so beautiful that many have been captivated. For, as Nietzsche has said, “if life were a dream, well then I’d as soon choose that one!” Later examination of mostly his letters suggest that Teilhard had a less than sympathetic view of many of the rest of us, the great unwashed who comprise the majority of those on the evolutionary journey towards the Omega point of the future. In fact there would seem to be required some considerable ‘ethnic cleansing’ before we can become sufficiently purified to gain entry to the golden circle of that ultimate Omega.

‘It’s author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself’”

Teilhard de Chardin tried heroically to introduce teleology into the universe with his Omega Point, but his vision has passed neither theological nor scientific muster . . . P.B. Medawar writes of Teilhard’s Phenomenon of Man. “It’s author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself.”

It is interesting to note that Teilhard worked for a while on the controversial Piltdown Man. This was a fraud in which bone fragments were represented as the fossilised remains of a previously unknown early human. Although there were doubts about its authenticity virtually from its announcement in 1912, the remains were still broadly accepted for many years, and the falsity of the hoax was only definitively demonstrated in 1953.

Fraudulent

An extensive scientific review in 2016 established that an amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson was responsible for the fraudulent evidence. In 1912, Dawson claimed that he had discovered the “missing link” between early apes and human beings. These finds included a jawbone, more skull fragments, a set of teeth, and primitive tools. Woodward reconstructed the skull fragments and hypothesised that they belonged to a human ancestor from 500,000 years ago. The discovery was announced at a Geological Society meeting and was given the Latin name Eoanthropus dawsoni (“Dawson’s dawn-man”). The questionable significance of the assemblage remained the subject of considerable controversy until it was conclusively exposed in1953 as a forgery. It was found to have consisted of the altered mandible and some teeth of an orangutan deliberately combined with the cranium of a fully developed, though small-brained, modern human. The Piltdown hoax is prominent for two reasons: the attention it generated around the subject of human evolution, and the length of time – 41 years – that elapsed from its alleged initial discovery to its definitive exposure as a composite forgery.

The Piltdown hoax stands as a cautionary tale which can similarly apply to the comprehensive theories of Teilhard de Chardin, who is even accused by some of aiding and abetting Dawson in his attempt to establish at least one missing link for the total Meccano set they were both trying, in their own well-meaning way to put on the market.

French Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin in 1955. Photo: Crux.

French Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin in 1955. Photo: Crux.