Today, the common question in spiritual circles is not, “What is your church or your religion?” but, “what is your practice?”

What is your practice? What is your particular explicit prayer practice? Is it Christian? Buddhist? Islamic? Secular? Do you meditate? Do you do centring prayer? Do you practice Mindfulness? For how long do you do this each day?

These are good questions and the prayer practices they refer to are good practices; but I take issue with one thing. The tendency here is to identify the essence of one’s discipleship and religious observance with a single explicit prayer practice, and that can be reductionist and simplistic. Discipleship is about more than one prayer practice.

A friend of mine shares this story. He was at a spirituality gathering where the question most asked of everyone was this: what is your practice? One woman replied: “My practice is raising my kids!” She may have meant it in jest, but her quip contains an insight that can serve as an important corrective to the tendency to identify the essence of one’s discipleship with a single explicit prayer practice.

Monks have secrets worth knowing. One of these is the truth that for any single prayer practice to be transformative it must be embedded in a larger set of practices, a much larger “monastic routine”, which commits one to a lot more than a single prayer practice. For a monk, each prayer practice is embedded inside a monastic routine and that routine, rather than any one single prayer practice, becomes the monk’s practice. Further still, that monastic routine, to have real value, must be itself predicated on fidelity to one’s vows.

Hence, the question “what is your practice?” is a good one if it refers to more than just a single explicit prayer practice. It must also ask whether you are keeping the commandments. Are you faithful to your vows and commitments? Are you raising your kids well? Are you staying within Christian community? Do you reach out to the poor? And, yes, do you have some regular, explicit, habitual prayer practice?

Monastic

What is my own practice?

I lean heavily on regularity and ritual, on a “monastic routine”. Here is my normal routine: Each morning I pray the Office of Lauds (usually in community). Then, before going to my office, I read a spiritual book for at least 20 minutes. At noon, I participate in the Eucharist, and sometime during the day, I go for a long walk and pray for an hour (mostly using the Rosary as a mantra and praying for a lot of people by name). On days when I do not take a walk, I sit in meditation or centring prayer for about 15 minutes. Each evening, I pray Vespers (again, usually in community). Once a week, I spend the evening writing a column on some aspect of spirituality. Once a month I celebrate the Sacrament of Reconciliation, always with the same confessor; and, when possible, I try to carve out a week each year to do a retreat. My practice survives on routine, rhythm, and ritual. These hold me and keep me inside my discipleship and my vows. They hold me more than I hold them. No matter how busy I am, no matter how distracted I am, and no matter whether or not I feel like praying on any given day, these rituals draw me into prayer and fidelity.

To be a disciple is to put yourself under a discipline. Thus, the bigger part of my practice is my ministry and the chronic discipline this demands of me. Full disclosure, ministry is often more stimulating than prayer; but it also demands more of you and, if done in fidelity, can be powerfully transformative in terms of bringing you to maturity and altruism.

Living in solitude

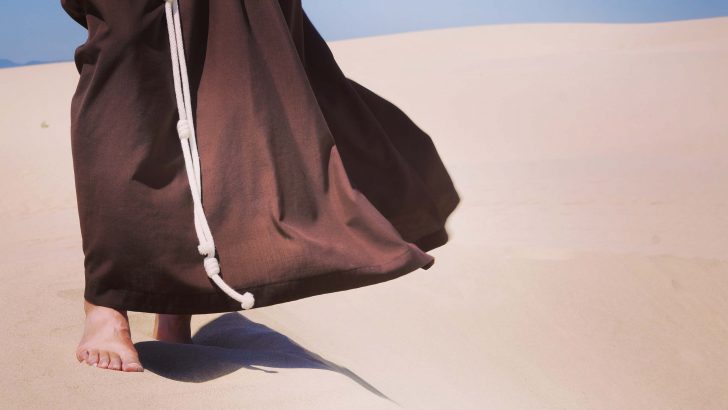

Carlo Carretto, the renowned spiritual writer, spent much of his adult life in the Sahara Desert, living in solitude as a monk, spending many hours in formal prayer. However, after years of solitude and prayer in the desert, he went to visit his aging mother who had dedicated many years of her life to raising children, leaving little time for formal prayer. Visiting her, he realised something, namely, his mother was more contemplative than he was! To his credit, Carretto drew the right lesson: there was nothing wrong with what he had been doing in the solitude of the desert for all those years, but there was something very right in what his mother had been doing in the busy bustle of raising children for so many years. Her life was its own monastery. Her practice was “raising kids”.

I have always loved this line from Robert Lax: “The task in life is not so much finding a path in the woods as of finding a rhythm to walk in.” Perhaps your rhythm is “monastic”, perhaps “domestic”. An explicit prayer practice is very important as a religious practice, but so too are our duties of state.

Fr Ronald Rolheiser

Fr Ronald Rolheiser