The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World

by Bart D. Ehrman (One World, £20.00)

Recently we have had several histories of early and medieval Christianity written from a very traditional Catholic point of view. These have in their way been very reassuring, but perhaps only by passing over darker passages in the development of a 2,000-year-old institution. This book takes a different approach.

Bart D. Ehrman is a professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina, and the author of Misquoting Jesus. Having moved from being a man of faith to an agnostic, he still finds himself (like so many) caught by the appeal of Christianity.

His many books are intended for a wide readership, and have proved both popular and enlightening to many. Yet he draws on the latest scholarship in the area, on ideas that might otherwise take decades to filter down to the pews.

He is the kind of writer who aims at clarity, and serves the general reader by setting the past both in context and in its relevance to this age we live. To those worried about the present day and the state of religion this may bring some insight, but also challenges to understanding, and the nature of belief.

Here he deals with the first three centuries of the Christian era. The book ends little more than a century before the death of St Patrick, a fact which sets it in the context of Ireland’s own religious history.

Struggle

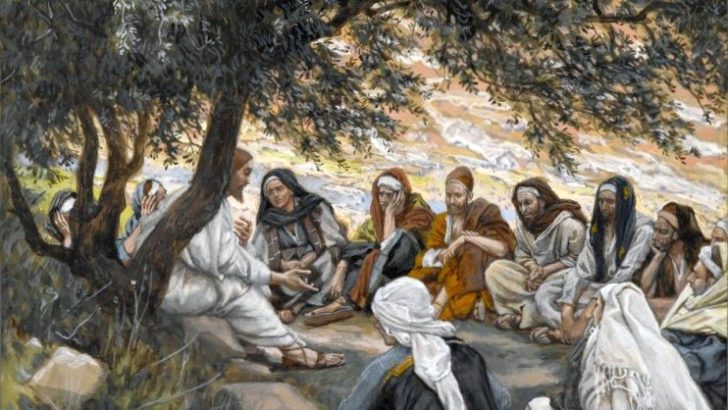

He opens with that struggle of those who had followed Jesus in his lifetime and ends with Constantine “the first Christian emperor” – though that is indeed a very ambiguous title.

He explains that the victory of Christianity, as promoted by St Paul, was not inevitable. Nor indeed by the ‘conversion’ of the Roman Empire could the new faith be said to have “swept the world”’ – in terms of mere population most of the planet remained quite as it was.

The global movement of Christianity from the Europe of Rome took much longer, and was never completed. As we face resurgent forms of Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, we can feel what it must have been like for the established religion of ancient Rome to feel itself under attack from an aggressive new faith.

Today, of course, many Christians in turn feel that they are also under attack from both aggressive new faiths in the religious sense, such as Pentecostalism, but also the secular sense, such as organised atheism. These are times then when many might need to relearn the confidence, and perhaps acceptance of the world, that gained Christianity a following in those early centuries among all classes of society, as the New Testament reveals, from the poorest of the poor to officials of the state.

What is best in early Christianity survives for us to make use of and can be found in the Gospels. Those things that were derived from the social attitudes of earlier times and the influences of other philosophies can now be put aside, in favour of a renewed understanding of the Gospel, what its saving grace might be in the approaching era when Christianity fully realises its nature as a religion among other religions, needing to gain adherents through the message that inspired so many in these early centuries.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello