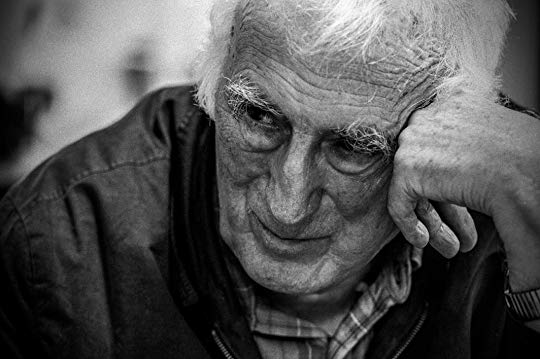

Revelations of psychological and sexual abuse of a number of women by Jean Vanier, founder of L’Arche, have sent shockwaves across the world.

Thoughts quickly turned first to the victims who experienced his manipulation and abuse, and who had been preyed upon when they were at their most vulnerable, seeking spiritual counsel; then to all members of L’Arche communities around the world who would now have to grapple with the cognitive dissonance of someone who was widely regarded as a saint having been exposed as guilty of an horrific abuse of power and status over many years.

There was also a grave breach of trust for those who encountered Jean Vanier more remotely, and drew inspiration from his books, lectures, spirituality and teaching.

For some, this has led to profound disillusionment; for others, hanging on by a thread to some connection to the Church, or even Christian faith, it will result in a walking away in disgust, perhaps for good.

Immaturity

I begin with a disclaimer: my knowledge of Jean Vanier was, and still is, quite limited. I never met him; I’ve never heard him speak; and I haven’t read any of his books. The closest I got to doing so was in 1992 as a 17-year-old seminarian when Mr Vanier’s Community and Growth was recommended to our first-year group as spiritual reading. I confess to not having got past the first few pages.

The fault, of course, was not with Mr Vanier, but my adolescent immaturity. So, no, I wasn’t familiar with his work. But here’s the thing, I am familiar with the work of many people who were. And these are people whose writings I greatly admire. People who quoted Mr Vanier on vulnerability. Who saw him as a bona fide spiritual giant (but, refreshingly, wearing the humblest apparel; no ego seemingly in sight).

And so, I admired Mr Vanier from a distance; second-hand, as it were, through the lens of the admiration of others, because I implicitly trusted their judgment. It was a case of “show me your admirers and I’ll tell you who you are”.

And that led me as far as occasionally sharing video clips of his wisdom on social media without having personally vetted them first (always a risky business). But Mr Vanier was kosher. His supporters (many of whom I myself admired, and whose spirituality I could identify with) told me so. Mr Vanier wouldn’t come out with anything embarrassing, or off-centre. He could be trusted to say the right thing; not to mention do the right thing.

His broad appeal crossed both confessional and religious lines. Although clearly a highly intelligent man, his message was essentially a simple one; and the core of that message was to be found in how he (seemingly) lived his life, placing the vulnerable at the heart of community living. When Krista Tippett interviewed Mr Vanier for the programme On Being in 2007, she described the rare quality of his presence as “wisdom in tenderness”.

As Jean Vanier’s reputation grew; and as he published a stream of books, embarked on lecture tours worldwide and participated in countless interviews, so his stature as a global spiritual authority became firmly established. This led to his being widely quoted by preachers, retreat-givers, pastoral care specialists, and spiritual writers. By the time of his death last year, and in the midst of a torrent of tributes from the great and the good, there were few who didn’t expect his cause for canonisation to open soon afterwards. But this would only be the official recognition of what so many already held to be the case.

Yes, we’d done it again. We had created a saint; ceremoniously placed him on a pedestal, and then looked up to him as another role model whose life was worthy of imitation. And, in doing so, we also helped create the cult of personality that surrounded him, despite his seemingly shy and retiring nature.

As ever, one of the most perilous of inclinations is towards the creation of a cult of personality. And, even more perilous, the cult of the spiritual personality. It was this that largely enabled Mr Vanier to behave in the way he did.

How could we have got it so wrong? Why couldn’t we have dared to look beyond the image we had created? For, no matter who a person is; no matter how wonderful their teachings; how marvellous their deeds; how beloved and admired they are; put them on a spiritual pedestal and you are bound to be disappointed. Always and without exception (to a greater or lesser degree). And this can often be devastating and utterly life-changing for those who have invested themselves so completely in the individual.

These recent revelations raise once more the dangers of the rush to canonise, something that we have seen particularly in recent years, most notably in the case of both Mother Teresa and Pope John Paul II. Regardless of one’s views on the saintly scorecard of either individual, there is a wisdom in letting our human dust settle.

The 16th Century reformer Martin Luther had quite an extreme view on human nature and its capacity to do good. He believed that all our good actions; even the greatest deeds of the most glorious saints, are, in and of themselves, mortal sins.

This is on account of the utterly tainted nature of humans as a result of sin, the tendency towards choosing the wrong things, which, for him, is itself sinful and something we can never shake off.

For Martin Luther, we love ourselves over and above all things; we seek our own advantage and to please ourselves in everything we do.

Whatever about Martin Luther’s seemingly pessimistic take on human nature, it does mean that, taken seriously, one could never hold any spiritual figure so aloft as to forget that, ultimately, we all have feet of clay (or, for Luther, we are clay through and through; indeed, he will put it a lot stronger than that).

Contrary to our cravings to canonise, there’s actually a great freedom in being taken down from a pedestal. It’s liberating both for the pedestal occupier and the pedestal gazer. It also allows mutual entry into the realm of honesty, reality and authenticity.

The rush to recognise a saint in their own lifetime is rarely a healthy move and can easily lead to disaster. In the recent film The Two Popes one cardinal is heard remarking in advance of a papal conclave: “The most important quality for a leader is not wanting to be a leader.” We could very profitably adapt this statement to the realm of saints: “the most important quality for a saint is not being recognised as a saint”.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the Jean Vanier revelations is how he used the language of spiritual mysticism to justify his actions to people whom he was supposed to be spiritually counselling; and in each case, where there was a hugely significant power differential at play.

***

The Church historian Hubert Wolf in his work The Nuns of Sant’ Ambrogio, set in a Roman convent in the 19th Century and based on an exhaustive study of records from the period, describes how the novice mistress, Sr Maria Luisa, a supposed visionary and mystic whose body was understood to exude a heavenly perfume, used her position of power and her reputation of sanctity not only to abuse young nuns sexually, but also to claim these abusive acts as signs of divine favour, during which she was communicating a blessing through her sanctified body.

Drawing on a meticulous study of Inquisition records, Prof. Wolf found that Maria Luisa had herself been initiated by a former abbess who saw herself as passing on the miraculous bodily favour of the convent founder Sr Maria Agnese Firrao, who established the religious house in 1806.

There are some stark parallels with the case of Jean Vanier. Here we have a revered figure, a man with an unquestioned reputation for sanctity, using his moral and spiritual authority to allow him to exert a psychological hold over women who held him in such esteem.

As in the case of Sr Maria Luisa, Mr Vanier’s sexual misconduct was often associated with alleged “spiritual and mystical justifications” as found by the independent investigation commissioned by L’Arche. According to one of the women he said: ‘This is not us, this is Mary and Jesus. You are chosen, you are special, this is secret”.

Another stated: “I realised that Jean Vanier was adored by hundreds of people, as a living saint who gave his support to victims of sexual abuse. It seemed like camouflage and I found it difficult to raise the issue.”

Also, as in the case of Sr Maria Luisa, Mr Vanier himself had been deeply influenced by a mentor, his ‘spiritual father’ Père Thomas Phillipe, himself a serial abuser who justified his actions with mystical claims.

What has struck many of Mr Vanier’s erstwhile admirers in recent days is not just the coercive psychological and sexual abuse which he was responsible for, but his ability to remain in denial that his actions were abusive, even when confronted by his victims. In light of what we now know, the following words of Vanier from his interview with Krista Tippett in 2007 are striking: “We don’t know what to do with our own weakness except hide it or pretend it doesn’t exist. So how can we welcome fully the weakness of another if we haven’t welcomed our own weakness?”

This quotation takes on a whole new meaning when, after the death of Père Philippe and the revelations concerning his behaviour, Mr Vanier preferred to remain in denial, stating in 2015 that he was “overwhelmed and shocked, absolutely unable to understand how this could have happened”. He went on to say that he was “unable to peacefully reconcile” the horrific actions of Père Philippe’s with the immense good done by L’Arche through him. So many feel the same today about Mr Vanier; although, in their case, they didn’t have the insider knowledge of these activities that he had.

***

So what do we do now? What do we do with all that wisdom that Mr Vanier shared during his lifetime? Is it still valid? Do his words remain wise or have they become null and void on account of what we now know; and henceforth devoid of value?

There’s one thing for sure – preachers, retreat-directors and spiritual writers, who routinely drew on Mr Vanier in the past, will keep clear of him in the future. Books by, or about, Jean Vanier will disappear from bookstore shelves. Institutions named after him will find alternative honorees. Words therapeutic have become words toxic. As Giles Frasier put it in a recent article in the online publication Unherd, “he has poisoned the well”.

This is an issue that has come to be much discussed in recent years, especially in light of the steady stream of abuse revelations concerning figures in the entertainment industry and the heightened awareness of this created by the #MeToo movement. Can, or should, one separate the artist from his or her art? Or as W.B. Yeats put it: “How can you separate the dancer from the dance?” Take, for instance, the following quotation from Mr Vanier’s Community and Growth:

“So many people enter groups in order to develop a certain form of spirituality or to acquire knowledge about the things of God and of humanity. But that is not community; it is a school. It becomes community only when people start truly caring for each other and for each other’s growth”.

Words that ring hollow in recent days.

This will be a question for the future; not for now. For now, whatever time is necessary will need to be given to the natural expressions of shock, anger, grief, and profound loss which accompany such revelations.

But, later, there is much to be discussed about trees and their fruits.

I issued a disclaimer at the beginning that I didn’t know Jean Vanier well, or his writings. But what I have known very well in the past are instances of the cult of spiritual personality. And I have long come to abhor it. In all its forms “deserved” or undeserved.

We’ve got to find a better way of relating to those we consider to be living saints; especially those with quasi-celebrity status. Better still, we would be well advised to stop this sort of nonsense altogether. Right now. It has never served us well in the past.

By all means, let’s learn from the simple faith, kindly behaviour and charitable actions of others and let’s try to incorporate these traits into our own lives. But let’s not create saints in their own lifetimes.

At its best, it serves neither us nor them, and often creates a slavish adherence to their every utterance, while collective critical faculties are anaesthetised. At its worst, it facilitates manipulative behaviour of alarming proportions, and opens the door to situations in which all kinds of abuse can flourish: psychological, sexual, and spiritual, leaving a devastating trail of destruction behind. Predators thrive on such adulation.

If the ‘saintly’ individuals in question are, indeed, the genuine article, this is surely what they would want in the first place (“not to us, not to us, O Lord, but to your name be the glory” – Psalm 115). If, by contrast, they are offended by our neglect of spiritual deference, then they will have unmasked themselves.

Perhaps this is also a salutary reminder to us to look for our role models closer to home; the everyday ‘saints’ who live in our midst. Those who do not lead global movements. Who are not invited to international events to walk among the great and the good as living icons of godliness. Who do not wield immense spiritual and moral authority by virtue of their very name.

Millions of people worldwide knew the name Jean Vanier and what he stood for; yet, I suspect few enough could actually claim to know the man himself. Really know him. The spiritual aura attached to figures such as Mr Vanier can make that very difficult.

And one more thing: can we ask that the sine qua non for ‘saints’ in the future simply be decent human being?

Salvador Ryan is a Professor of Ecclesiastical History in St Patrick’s College Maynooth.