Fully alive: Tending to the Soul in Turbulent Times, by Elizabeth Oldfield

(London: Hodder & Stoughton, £18.99 / €26.99)

Elizabeth Oldfield directed the London based ‘think-tank’, Theos from 2011 to 2022. Established in 2006 with the support of Cardinal Murphy-O’Connor, the then Archbishop of Westminster and the then Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, Theos researches issues of public concern within a Christian perspective, giving voice to the Christian tradition in the public square.

We can distinguish between contestation and conversation. To contest is to enter into argument to correct error and clarify truth, to converse is to bring what you see in your horizon into the horizon of “an other”. The common ground found in this merging of horizons delivers shared understanding even if it does not produce agreement. Theos’ style is conversational and Oldfield’s book is a marvelous example of that style.

Principles

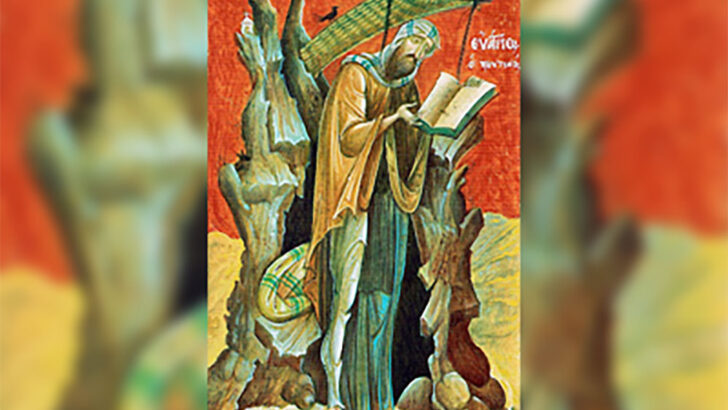

The book, she tells us, is ‘designed for those in search of spiritual core strength who are curious about what the practices, postures, and principles of Christianity might teach them’. She does this in an examination of the deadly sins listed by Evagrius Ponticus (345-399AD). An eccentric choice, one might think when sin hardly figures, if at all, in secular discourse where concern with “self-esteem” rules out attention to our “grievous faults”.

While Catholics continue to recite the confiteor, I cannot recall when I last heard a sermon on sin. I suspect I am one of the last generation who could even make a stab of listing them: wrath, avarice, acedia, envy, gluttony, lust and pride.

I learned in primary school that sin is what offends God, merits punishment and will be forgiven. This is not a good starting point for developing an adult understanding.

Oldfield anchors her account in her own experience and the ways in which we mess things up, frustrating our desires and damaging our relationships. She weaves, with considerable intelligence, psychological insight, sociological sense and the wisdom of the tradition together to bring the reader into the world where the particular damage each sin does to our flourishing is clearly visible, our weaknesses are laid before us, our culpability for the way things can go wrong for us, exposed.

We make a “hell” for ourselves by the ways in which we distort our relationships with others and the world about us”

Sartre’s assertion that “hell is other people” is an extreme example of the common fear that our relationships threaten our autonomy, restrain our freedom and expose us to the danger of exploitation.

While Sartre and our culture put the individual first, Oldfield puts relationships first. She supposes, correctly, that individuals emerge from relationships in which our capacities for autonomous action are formed. We make a “hell” for ourselves by the ways in which we distort our relationships with others and the world about us. And the deadly sins describe these.

Value

I am sure that she succeeds in convincing the non-believer that there is much of value in the Christian account of sin. Believers too, will learn much from this persuasive telling of part of their tradition that is confined to the shadows. But a question remains.

The notorious atheist Richard Dawkins has recently declared himself a “cultural Christian”. Although he continues to believe that talk of God and revelation is nonsense, he finds norms promoted by, and insights found in, Christianity worth preserving. Has Oldfield done more than contribute to “cultural Christianity” ?

Where is God in her account? Proving the existence of God is high on the agenda of those who contest the atheistic, scientistic foundations of our secular culture.

Endeavour

Believers benefit from this endeavour. It strengthens their faith and protects them from the temptation of supposing God is some sort of super-hero, the biggest most powerful object in the universe. The creator is not a creature. I doubt, however, if any unbeliever has been brought to believe by these arguments.

If the deadly sins describe the hell we can make for ourselves, they also indicate the happiness we can find in human flourishing”

So, Oldfield wisely leaves such considerations out of her conversation. She wants to show what “believe in God” means by recounting what it has meant for her. It is a relationship founded on the experience of profound love and it transforms what could have been a despairing picture of the misery of the human condition.

To recognise the damage a sin does is at the same time to recognise a good it frustrates. If the deadly sins describe the hell we can make for ourselves, they also indicate the happiness we can find in human flourishing.

The story Olfield tells of faith lost and found, of the rewards and difficulties of family, work, living in community, is also a story of how God’s love transforms. Responding to that love in striving to love our neighbour, the good that our nature can attain comes into view and we move closer to its realisation.

The non-believing reader seeking ‘spiritual core strength’ is lead to the thought that we need saving and salvation is at hand. The believer will find their understanding of redemption renewed and deepened while being encouraged to renew their efforts.

Oldfield’s chatty, relaxed style which makes for an easy read is rooted in a deep theological understanding and a firm philosophical grasp.

Evagrius Ponticus

Evagrius Ponticus