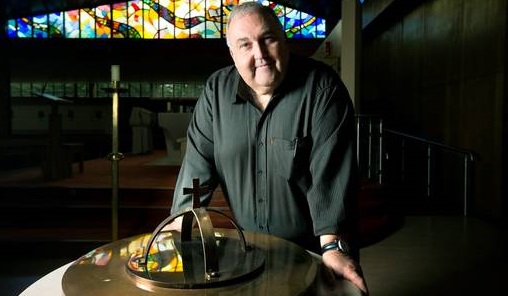

Why the Irish Church Deserves to Die. Ballyfermot-based priest Fr Joe McDonald could hardly have chosen a more inflammatory title for his first book, calling for Irish Catholics to embrace the reality of a dying Church and work for a resurrection.

The title’s not idly chosen, he says, explaining how there’s a point in the book where, looking at the state of the Church in Ireland, he raises almost a medical question. “Where are we going with this body? Are we making for intensive care? Or have the lights gone out? Do we not take a bed in intensive care, and get this Church to the morgue?”

The situation is, he says, that serious. “And the bit that people will not like, which of course is contained in the word ‘deserves’ – it’s a very different word than if you say ‘the Irish Church needs’, ‘the Irish Church may’, or ‘will’, or ‘should’, or ‘could’. ‘Deserves’ is uncompromising, and some of my closest friends pulled back from that, saying they’d go with it all except for that, but the word is essential,” he says.

Ordained

Born in Belfast in 1961, the eldest of four siblings, he was a Christian Brother before being ordained as a priest for the Archdiocese of Dublin, where he has been parish priest at St Matthew’s in Ballyfermot for the last five years. Not, he necessarily thinks, that Ballyfermot’s three parishes – like so many others across the archdiocese – have a sustainable future in their current form.

Archbishop Diarmuid Martin, he says, is “very very gifted, he has great talents, but I think his successor is going to be faced with some very, very hard decisions”.

Things certainly can look hopeless on the ground. He described how someone recently asked whether, though he comes across as a happy priest, he is ever sad.

“They expected me to go down the road of maybe celibacy, life without a wife or all that,” he says. “Sadness for me would be to meet people, the majority of whom have spent maybe 12, 14 years in Catholic school, primary and secondary, and some of them indeed third level in Catholic training colleges – sadness for me is to meet them and to realise they really have no sense of the person of Jesus.”

It amazes and depresses him, he says, that despite years of one sort or another of Church involvement, people tend to lack passion and vibrancy about Jesus himself.

“I say things about cultivating a personal relationship with Jesus, and they say ‘how can you cultivate a personal relationship with somebody who died 2000 years ago?’” he says, stressing that people don’t seem to get that it’s a relationship that’s given reality when you put work into it – when you try.

“If it wasn’t a reality for me, I wouldn’t last. I certainly wouldn’t last as a priest,” he says.

Fr Joe opens his book by drawing on the Canadian singer Neil Young’s 1979 album title Rust Never Sleeps to point to how regardless of what’s happening on the surface there are undercurrents that are hitting the Church in unseen ways.

“In a way that’s where things really kicked off, with this idea of rust. That idea that there’s something going on, almost sleeping, that we’re not quite tuning into,” he says. “We talk about measurable things – there was a fall in Mass in that parish, and there’s no vocation from that diocese in this year – and we talk about those things but don’t really get into what’s going on underneath. I describe that –the reason I like the rust image is that the rust is working away there unbeknownst sometimes behind paint or whatever, weakening a girder, weakening a key part of the thing. What I’m talking about is the whole underlying thing of the loss of the sacred, a loss of the mysterious.”

There can be a real tendency, he says, to focus on measurable answers to questions about what is happening and when things happened, without going further and asking why. Instead of asking how many people go to Mass in a certain place at a certain time, he says, maybe we should be doing more to ask why – even if the answers might be uncomfortable for individual priests.

“Because the terrible thing in Church life, particularly for guys like me, is that we’re unaccountable,” he says. “I’m not even talking about an abusive clericalism. It’s just: if I was really making a hames of it, would I know? Would I really know? You’d like to think somebody would be flagging something with you, but people are very tolerant – I don’t think it’s that old style fear of the priest, but people don’t want to hurt your feelings: they know that you’re on your own, without the support of a wife and family and whatever, and they make allowances for it, for us. And that’s a nice thing in one way…”

At a national level, he says, a serious problem is the bishop’s conference and the nature of the hierarchical Church.

“Don’t get me wrong – I have no desire to be having a go at a particular bishop or a group of bishops. I know they’re good guys,” he says.

The problem, he says, is shown by things that aren’t really controversial. “We have been talking for 20 years, possibly 30 years, way before I was ordained as a teaching brother, we have been talking about the problem of confirming 80 children and seeing eight of them in the coming weeks, or giving Holy Communion to 60 children and seeing six of them,” he says, pointing out that something as basic as this hasn’t been tackled, adding that whenever answers are proposed at a local level, they’re dismissed on the basis that solutions would have to be national.

Disparate Group

“If you keep saying ‘no we can’t, because you need the bishops to agree’, the problem is that they cannot. Not trying to sound harsh or judgmental, but because they’re a disparate group and they meet a few times a year, and you know, they set up a sub-committee or whatever, it’s dysfunctional in the sense that doesn’t produce the decision, it doesn’t produce the working thing that we need to do, so it becomes a catch-22 – we can’t do it without the bishops, and the bishops can’t do it, so what do we do? And we keep spinning round and we’ve lost another generation and another generation.”

Time, he says, is running out, with the days when you could “rely on the grannies” having passed and graduates of Catholic training colleges likely to define a Catholic ethos in generic – even humanist – terms. It’s not enough, he says, to relax and point to Christ’s promise that the Church will survive, since he never promised it would survive in any given place, or any given time, so action needs to be taken.

“Our time is limited. I’m saying that if we keep talking about it our time will pass us by. It’ll get to the stage where what can be retrieved is minimal. If we think that this Irish Church can’t die, then there’s an arrogance and a denial.

“It died in France, clearly; people say there’s a Church in France, and there is, but it’s a very, very different Church,” he says.

Greg Daly

Greg Daly Fr Joe Mcdonald

Fr Joe Mcdonald