The Oldest Books in the World: Philosophy in the Age of the Pyramids, by Bill Manley (Thames and Hudson, £25.00/€29.00)

How could any literate person resist the appeal of a title like this? Here for once they will find their expectations brilliantly fulfilled.

This is indeed a most interesting book, but more than that it will I suspect be a book of some future importance to those interested, not just in ancient Egypt, but also concerned with the origins of philosophy, as well as the influence, so little considered in the past, on the emergence of Christianity in its first centuries. But the key to the matter is the sudden introduction of writing, and its rapid adoption.

Bill Manley is a well-established academic having taught the languages of ancient and Christian Egypt, over 30 years at London University, Glasgow and Liverpool, among a variety of related activities as curator and popular lecturer. I say this so as to reassure readers that this is not what my son calls “a crank book”.

Details

Far from it indeed. Page after page is filled with mind-changing details. Take for instance the fact adduced here that this earlier book of all conceives not an array of gods, but a single creator.

Manley presents Akhenaton, far from the manipulated legend of being “the first individual in history” and all the familiar tropes we find in Thomas Mann, Sigmund Freud and others.

It seems we may have to rethink the common view about the mental life of the Egyptians. Monotheism seems to have an earlier horizon than usually thought, moving back into the Neolithic. But first the background, which is fascinating.

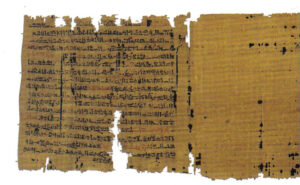

The period here is circa 2400BC. What the author describes as the world’s earliest book is The Teaching of Ptahhapt. This, in the form of Papyrus Prisse, was first printed in Paris in 1858, but ever since, aside from a very few scholars, has been ignored. Most scholars ignored it, or said it impossible to translate and was unintelligible.

It is a collection of maxims rather than a discussion or essays, such as we are familiar with in Greek or classical philosophy generally. It bears no resemblance to the polytheistic or even occult nature of what people imagine Egyptian literature to consist of.

It provides counsels of action and for living which are very clear. One of his main thoughts is to avoid purposeless debate or angry exchanges – with which we are now over familiar – as they are quite fruitless. We should learn continually from others, and not always seek to impose our notions on others. It even gives advice for office life, and bosses should act, for the litterateurs at that date were largely engaged in the administration of the state for the pharaoh. This maxim could apply today.

But aside from maxims of good counsel, the present book includes, from another papyrus, a new translation of Why Things Happen, about the nature of the physical world, and the creation of the world and how it works in an ordered, creative way.

Manley argues that writing was a sudden introduction, and that Ptahhapt is the first named writer in the world. The new invention of writing changed the Egyptian world. Just as the PC spread in a couple of decades, so too writing seems to have suddenly and shockingly emerged as the major influence on society. Already the writer could challenge the kings of the world.

It is surprising to read this, for having always been taught that the Egyptians were polytheistic we find in fact the authors of these texts conceived of, not countless gods and spirits, but essentially a creator above and beyond the deities of the Nile Valley. Essentially Ptahhapt was a monotheist.

Connects

This connects him forward in time, as Manley observes, with the author of The Gospel according to John, especially its opening passage.

“In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God”: that so familiar locution, it seems, was basically an Egyptian expression of belief.

This set me off on a line of thought which I have little room to discuss here, of the unsuspected influence on Jewish and Christian thinking; another day perhaps.

Peter Costello

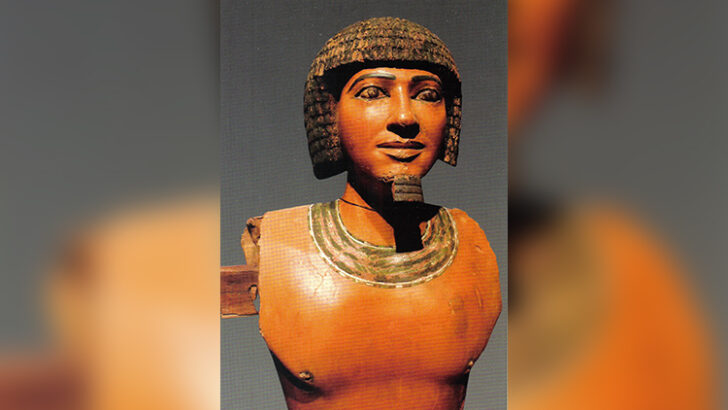

Peter Costello Ptahhapt, a life-size portrait , plastered wood, 5th dynasty.

Ptahhapt, a life-size portrait , plastered wood, 5th dynasty.