With God You are Never Alone: The Great Papal Addresses, by Benedict XVI (Bloomsbury, £14,95 / €17.50)

In this book, which is bound to secure a wide readership, the 10 most important speeches of the Pontificate of Benedict XVI, are collected by Fr Federico Lombardi, of the Ratzinger-Benedict Foundation in Rome.

These speeches reveal the outlook, the scholarship, and the human warmth of Pope Benedict on a variety of important occasions. They will be read, in some cases reread, with great interest and attention.

In the promotion of the book, Fr Lombardi makes an important comment. “Dubbed and dismissed by many as an unrepentant traditionalist, we now see a man of profound intelligence and wisdom on matters relating not to just to religion but on what is now termed ‘The Common Good’.

“It is thus more important than ever to read these texts carefully and with measure and not in garbled versions dreamt up by the press. With this in mind, Benedict will be seen as an inspiring thinker who has a lot to teach us now and in the future.”

This will give some pause for thought. These are addresses, texts prepared not to be read but to be listened to. What is heard cannot be studied carefully, the words must act directly and at once. There is a difference between a thesis and sermon.

I suspect that this failure to understand the nature of an oral address that gave rise to the public confusions and debates that so dismayed Pope Benedict, by character a reserved and scholarly man.

Take for instance the address in which he made know his decision to resign the papacy.

This was announced to an audience in Latin. In the film of the occasion one can see the slow wave of reaction, for clearly the majority were unable to grasp as he spoke the nature of what he was saying.

But then the realisation began to ripple though the assembled ranks. He ended leaving in the minds of many who heard him, both clergy and press great confusion of mind.

The ‘versions’ were not really dreamt up by the press in a malicious way. The Papal staff had not prepared the group for the announcement, nothing was issued to shape the world’s reaction.

The same was true of the Regensburg address which was very quickly fanned by the media, written and visual, into an anti-Muslim attack, which it was very far from being. Benedict was clearly unprepared for this.

There was nothing, to his teacher’s mind extraordinary about what he was saying. But without a text already in hand his audience were left confused. If he had been speaking to an audience of university students there would have been no media eruptions. But what he said all too easily, and quite contrary to his intentions, played into the hands of Islamic critics of Rome.

But following Lombardi’s injunction a careful reading of the pope’s words does indeed reveal an extraordinary man, with a very clear lines of thought. Even all his years working with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, seems not have laid the groundwork for a public style.

This was the world’s loss. For in an atmosphere of calm consideration, he emerges for what he was, a good, kindly minded man sensitive to the moods of faith and the varied experiences of God, in fact a holy man. But not perhaps a man for the conflict of today’s media with its almost immediate grasp at a hint of conflict.

His life’s work as an academic will come to be seen as great intellectual resource. But which will be read and absorbed in hours of quieter reflection as their author intended.

Peter Costello

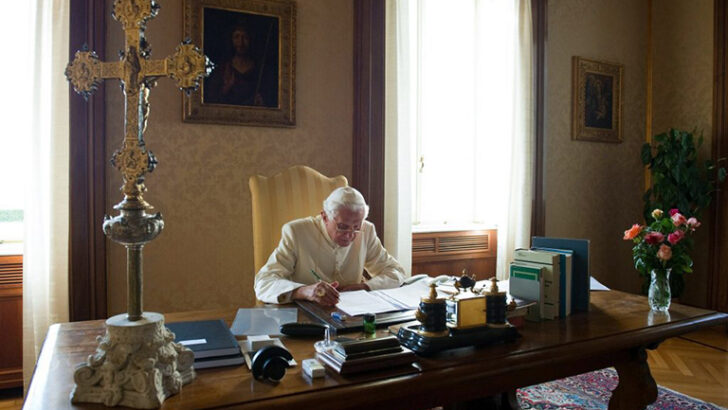

Peter Costello Benedict absorbed in work in his study.

Benedict absorbed in work in his study.