Silence and Thomas Merton

The Powerball Lottery in the USA has been much in the news recently, partly because of the huge prize on offer to the lucky winner, or it seems, winners: $1.6 billion. Just think of that in terms of aid for famine and flood victims. What could an individual not do with it? Spend it foolishly perhaps?

One past winner from 2014, Roy Cockrum, of Knoxville Tennessee, had a different notion.

Having once been an Episcopalian monk himself, he decided to fund a play about Thomas Merton, the Catholic monk, writer and activist, much admired around the world, for such books as Seven Story Mountain (also known as Elected Silence). He set up a foundation which would use the money to support not-for profit theatre to stage plays with a spiritual or philosophical theme.

Through a production company named Knight Blanc (doubtless after the wise fool in Alice in Wonderland) he aided The Glory of the World, a production of a theatre group in Louisville where Merton’s own monastic community was, to New York City. It opened last week at the Brooklyn Music Academy.

The author of the play is Charles Mee, who is also an historian. It was mounted originally in Kentucky in 2015, the centenary of Merton’s birth.

It has a cast of 17 men and is set at a sort of centenary birth party for Merton, who does not appear, though perhaps through the character of Les Waters, who comes on at the opening and remains on stage for a long time in silence before a screen on which is projected “Crunch of the shoes on sidewalk / Like the sound of peanuts being cracked”.

Audiences found this strange and then intimidating. But soon the stage filled with 17 players, representing different points of view and the exploration of themes related to Merton’s thoughts and outlook begins. The speakers fall at one point into a 14-minute stage fight, before what Mee calls “the party” proceeds.

Local reviewers, much like the audience, were puzzled, supportive of the actors ability, but doubtful about what was being communicated.

Charles Mee is on the record as saying about Merton: “Everybody is far more complicated than that one simple line about being a great mystic, a great Buddhist, a great activist, whatever.”

That’s very true. But there still seems room for a play – perhaps a more boringly traditional one – which would explore more directly Merton’s experiences, thoughts and visions. These days playwrights rarely take religion, faith, and visionary experiences – even those of William Blake – seriously.

On his American visit last year Pope Francis, in his speech to Congress, identified Thomas Merton – to the dismay of conservative Catholics across the US – as an exemplary American from whose wisdom the whole world can learn: “Merton was above all a man of prayer, a thinker who challenged the certitudes of his time and opened new horizons for souls and for the Church. He was also a man of dialogue, a promoter of peace between peoples and religions.”

Charles Mee is a former Catholic and grew up in a house filled with Merton’s books. He told producer Waters, even before he began the play that, unlike the Pope, he “couldn’t write anything nice” about Merton. This seems an odd approach. Surely a true theatrical exploration of the vision and thought of Merton would find in its complexity, not a more balanced view perhaps, but a more nuanced one. In that sense Mee’s work is strangely self-limited.

Here surely is a chance for a younger Irish playwright. And who knows, with the giant prizes now pouring from own National Lottery these days, perhaps some Maecenas would come forward in the same spirit as Roy Cockrum, to fund the production. It is hard to imagine such a thing at the Abbey or the Gate. But then miracles – or what the world would prefer to call strange things – do happen, especially in the theatre.

Thomas Merton’s famous first book, the spiritual autobiography Seven Story Mountain (1948), is available in a special Centenary Edition (SPCK, £20.00). Many of his later books remain in print as well.

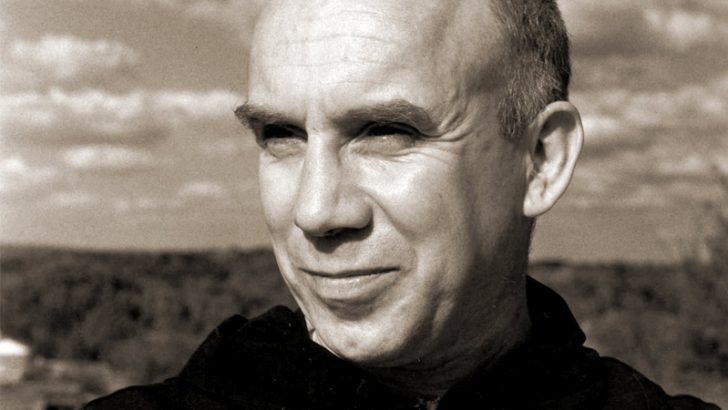

Thomas Merton

Thomas Merton