A Co. Kildare doctor, Adrian McGoldrick, who is recovering from the coronavirus, has warned others that an attack of Covid-19 can leave them with heart conditions and other health issues.

“Don’t think that you can get the virus and that you will not suffer,” he has said. “Treat this virus with respect…this is going to be with us for years to come.”

Dr McGoldrick, aged 67, felt drained of all energy when he succumbed to the virus. He was so fatigued he couldn’t hold a phone in his hand. Subsequently he was diagnosed with myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle which can affect Covid-19 patients. He is recovering but still spends up to 12 hours a day in bedrest.

A salutary caution to anyone who takes an overly casual view of the pandemic: if you get it, you will suffer.

But even if you don’t get it, you will suffer from something else. Hasn’t Dr McGoldrick read the famous saying of the Buddha: “Life is suffering”?

Looking back over my own stretch of years, I can perceive that in every life there has been suffering; sometimes of physical illness, and towards the end of life, nearly always so.

Don’t take coronavirus lightly, or dismiss it as a touch of flu”

And often with emotional, spiritual and mental illness too – loneliness, loss, terrible bereavement by sudden accident or even homicide, addiction or psychotic conditions, plus divorce, abuse, abandonment, suicide of a loved one.

I saw my husband decline over 12 years, through a series of strokes, changing him from an active man to a helpless invalid. My best friend was killed by an arsonist, leaving a young son. Another close friend was murdered, along with his daughter, by his own schizophrenic son, causing a series of family tragedies. My beautiful niece died in her prime from a brain tumour. I’ve seen suffering by cancer, Parkinson’s disease, bewildered dementia and late-onset blindness.

Suffering is the human condition: “Take up your cross and follow me.”

This is not to diminish the valid point that Dr McGoldrick makes: don’t take coronavirus lightly, or dismiss it as a touch of flu.

But the truth is that there is always suffering in this life – a truth that has been studiously evaded in a culture which prioritises comfort and ease.

We need to know that truth, and to develop fortitude to face it.

Guinness certainly did ‘good’ for Irish society

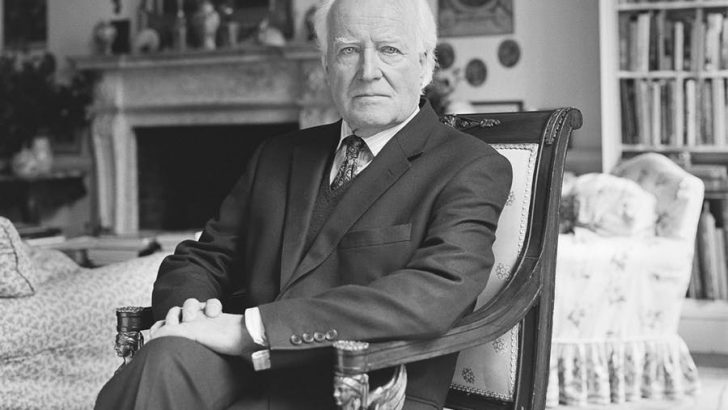

The passing of Desmond Guinness is a moment to reflect on what he did for Ireland’s Georgian heritage. With his German-born wife Mariga, Desmond galvanised the forces that preserved a heritage that was otherwise neglected, or destroyed.

Apart from the great houses, Mountjoy Square in North Dublin is, for me, his monument, saved from the wrecking ball by his and Mariga’s endeavours. These are amazing houses – the proportions inside the front hall, alone, are breathtaking.

I only wish the Irish Georgian Society could have saved those former tenements in Lower Gardiner Street, where Seán O’Casey set his most memorable plays. They could have been restored for housing purposes.

Preservation

Back in the 1960s, I was alerted to the Georgian preservation cause by the campaigns of the Jesuit, the late Fr Michael Sweetman, who was deeply involved with housing for the urban poor – but also campaigned to save Ely Place, just off St Stephen’s Green.

Fr Sweetman didn’t see the cause of preservation of housing stock as ‘elitist’ – it was part and parcel of housing and history. He was attached to St Francis Xavier’s in Upper Gardiner Street, and he elected to live in nearby Summerhill, then regarded as a slum area.

Desmond Guinness was the son of the philanthropic Lord Moyne and the more controversial Diana Mitford, who subsequently married the British Fascist leader Oswald Mosely.

It was said of Des-mond, who could be mischievously amusing, “that the Good Guinness and the Wicked Mitford battled in those blue eyes”. The Good Guinness usually won.

He certainly did good for Ireland’s architectural heritage.

A kind neighbour is a great friend

In my enforced absence from Dublin – I was officially warned not to travel to my native city during the summer – the studio flat that I rent has been broken into. I am an unrewarding object for a burglar since I possess little of material value. My jewellery is cheap and cheerful bling, I have no TV and my technology is 1970s – CDs and even cassette tapes.

However, what I do have is a wonderful, kind and altogether Christian Catholic neighbour who takes care, takes responsibility and helps to sort things out with sunny competance, and that is more valuable, surely, than rubies.

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny Desmond Guinness.

Photo: Amelia Stein; courtesy Irish Georgian Society

Desmond Guinness.

Photo: Amelia Stein; courtesy Irish Georgian Society